Thinking about real world problems is impossibly hard. Any story you tell yourself about the world is necessarily an abstraction.

What does the world abstraction mean? The Merriam-Webster dictionary tells us that “from its roots, abstraction should mean basically “something pulled or drawn away”.” So when you tell yourself a story about the world, you are pulling something, or drawing something away from reality.

What are you drawing away from reality? The parts of reality that seem important, interlinked and informative to you. So for example, when you wonder why the prices of onions are so damn high, you try to “pull” out of our reality those parts that you think will help you explain why the prices are so damn high.

Now, you are the captain of this ship – the one that is about to undertake this intellectual voyage of discovery. You are free to taken on board any parts of reality that seem relevant to you. Unfortunately you cannot take on all of reality, because then, hey, you aren’t pulling or drawing something away from reality. You’re trying to take on all of reality! And that is difficult impossible to do.

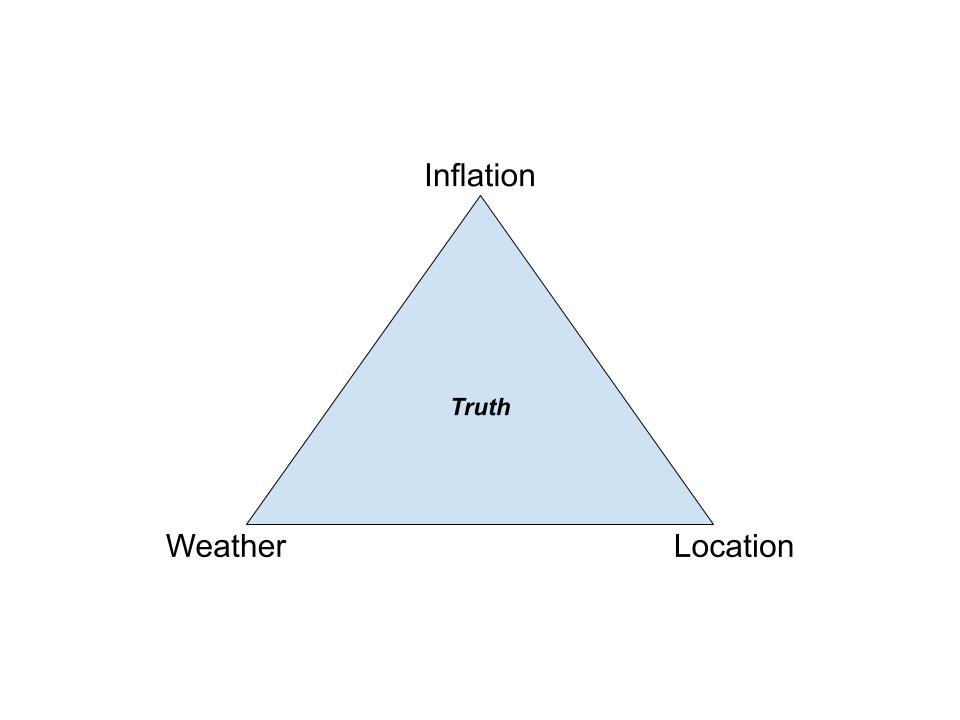

So you might choose to take on weather patterns, inflation, and the part of the country that you live in. These might help you arrive at a way to think about this specific real world problem: what is causing the prices of onions to be so high? Could be, you think to yourself, because of unseasonal rains, could be because of high inflation and it could be because you live in a tony part of a town/city that tends to have high prices of vegetables.

Congratulations, you’ve built a mental model! Don’t worry (yet) about whether the model is correct or incorrect. Don’t worry about whether you can gather the data required to test out your model. Don’t worry about whether the model will work next year, or in another part of the country. You’ve fashioned for yourself a story, and the story goes like this: x is seen in the world because of y. Specifically, high onion prices are seen in your world because of the weather, because of inflation and because you live in (say) Pune.

Savor this moment of victory, for we’re about to add in some complications.

The first complication is that you haven’t taken into account everything that influences the prices of onions. Maybe there’s a transporters strike? Maybe there’s been a pest attack on onion crops? Maybe a restaurant in your area has purchased an unusually large quantity of onions just a little before you went out to buy onions? Maybe the vendor was in a bad mood, and is charging you high prices for no good reason?

Some of these questions make sense, others do not. My point is that once you start to think about the problem in greater detail, you might realize that there are many other things apart from your three factors, that at least have the potential to raise onion prices.

But pah, you say to yourself. By this logic there will be no end to this exercise. You have, you tell yourself, chosen the factors that are likely to explain most of the increase in prices. Sure, you say to yourself, there are other causal factors out there. But these three? These, you aver to yourself, do most of the heavy lifting. And so you have chosen to “pull out of”, or “abstract away from”, reality these three alone.

A good modeler always bears two things in mind, therefore: her skill is about identifying((and then verifying – this exercise us economists call econometrics, and we get very excited about it)) the factors that are most important. But a good modeler also always worries about whether she has missed an important factor. A good modeler therefore always walks that painfully thin line between certitude and hubris. And this is hard.

But now we’re faced with a new problem. Of the three factors that we have chosen, which is the most important? Is it all about weather, and not at all about inflation and location? Or is it almost entirely about inflation, and not so much about the other two? Or… you get the drift.

Which, finally, brings us to the point of this essay: The Truth Always Lies Somewhere in the Middle. Corner solutions aren’t impossible – it is certainly possible that it is only the weather that is causing the prices of onions in your neighbourhood to be so damn high. But I would say that it is unlikely. Location almost certainly is an influencing factor. And so also is inflation.

In fact, it’s worse, because for reasons discussed above, the truest shape to surround The Truth is some impossibly complicated polygon. We’ve chosen to abstract away from this polygon only three factors, and so we have the luxury of thinking about where The Truth might lie in this triangle.

But even in this simplified model, we should fight the urge to corner The Truth into a single vertex. It’s almost always more complicated than that.

- Is Thai cuisine good or bad?

If you were to ask me, good! But are there Thai dishes that I don’t like? I should be clear: this is not a dish I have eaten, but I (unfortunately) have a mental bias against even trying this dish. Given what little I know of Thai cuisine, the loss is almost certainly mine – but hey, it is what it is.

So is Thai cuisine good or bad? If you were to ask me now, after that last paragraph, almost entirely good.

You see how what I choose to abstract away from reality helps me learn more about where The Truth might lie? - Is Sachin Tendulkar a great batsman?

In my opinion, almost definitely so. Now, I’m a Sachin acolyte. But even I, a rabid Sachin fan if ever there was one, know about his fourth innings average. I know that McGrath got the better of him in ’99 and (sigh) ’03. And so on and so forth. So on the Great-Not Great spectrum, I would place him very very close to the Great end of the spectrum.

Reasonable people can and should disagree about where on the spectrum The Truth lies. But a discussion becomes impossible, and therefore counterproductive, if you insist on clinging to just one tiny little dot in reality called Great (or Not Great).

This applies to economic models, political leaders, vaccination policies, American Presidents – and Thai cuisine and Sachin’s greatness, and everything else besides.

The Truth is mostly unknowable (and that is bad enough). But for us to have the hubris to think that we can pin it down to just one part of a binary is an extremely dangerous thing, and I think we would all do well to try and not fall into that error.

What explains the title of this post?

Well, I have Aadisht to thank for it. He has noticed, as perhaps you have, my tendency to use this phrase quite often in my posts here: The Truth Lies Somewhere in the Middle. Now, the abbreviation of this phrase doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue easily. TTLSITM isn’t likely to win me any marketing awards, alas.

But consider this magnificent wordplay:

Truth Always Lies Inexorably Somewhere in the Middle of Assertion and Negation

That’s a talisman I’m very happy to claim ownership of!

There just remains the small matter of deciding upon a suitable compensation for Aadisht’s time and expertise. But if you think about it, the idea was mine, and it was just the acronym formation that he contributed.

So between refusing to even acknowledge his contribution and giving him all the credit…

“This applies to economic models, political leaders, vaccination policies, American Presidents – and Thai cuisine and Sachin’s greatness, and everything else besides. !! ” Great one once again.- Prachi Kulkarni

LikeLike

As always, inspiring and thought-provoking.

As I was reading, I thought that this idea in itself is embedded in econometrics. We strive for 100% R-square or the lowest p-values. What is this all about? Nothing but the journey to find the truth or from one end of the spectrum to the other.

“So on the Great-Not Great spectrum, I would place him very very close to the Great end of the spectrum.” That is us proving something by trying to find the truth (higher R-square).

What if we change the variables? Sometimes, R-sq changes from 50% to 80% and we are happy, and sometimes, it falls to 25%. If we equate R-sq with the point on the spectrum, then we moving along that line – sometimes towards the truth, sometimes away.

But finally, we accept the reality. We cannot incorporate all variables and be at end of the truth spectrum. So, we accept the reality and that is, even if R-sq is 60+, we are happy.

So, in a way, truth is always somewhere in the middle.

LikeLike