If the plastics industry is following the tobacco industry’s playbook, it may never admit to the failure of plastics recycling. Although we may not be able to stop them from trying to fool us, we can pass effective laws to make real progress. Single-use-plastic bans reduce waste, save taxpayer money spent on disposal and cleanup, and reduce plastic pollution in the environment.

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/05/single-use-plastic-chemical-recycling-disposal/661141/

Consumers can put pressure on companies to stop filling store shelves with single-use plastics by not buying them and instead choosing reusables and products in better packaging. And we should all keep recycling our paper, boxes, cans, and glass, because that actually works.

Those are the concluding paragraphs from a write-up in the Atlantic about how plastic manufacturing firms have been, shall we say, less than perfectly honest about their ability to actually recycle plastic.

You may or may not agree about the harm done to the environment due to singe-use plastics, but for the purpose of this blog post, please assume that this is a problem you want to try and mitigate. How might you go about it?

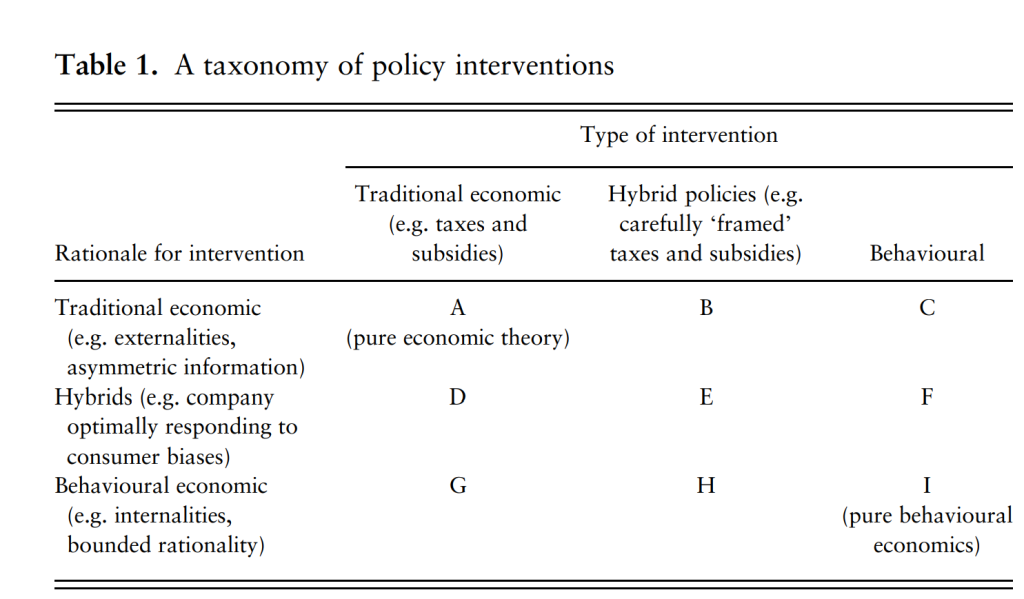

Chater and Loewenstein say that behavioral economists and policymakers have been getting it all wrong:

An influential line of thinking in behavioral science, to which the two authors have long subscribed, is that many of society’s most pressing problems can be addressed cheaply and effectively at the level of the individual, without modifying the system in which individuals operate. Along with, we suspect, many colleagues in both academic and policy communities, we now believe this was a mistake. Results from such interventions have been disappointingly modest. But more importantly, they have guided many (though by no means all) behavioral scientists to frame policy problems in individual, not systemic, terms: to adopt what we call the “i-frame,” rather than the “s-frame.” The difference may be more consequential than those who have operated within the i-frame have understood, in deflecting attention and support away from s-frame policies. Indeed, highlighting the i-frame is a long-established objective of corporate

Chater, N., & Loewenstein, G. (2022). The i-frame and the s-frame: How focusing on the individual-level solutions has led behavioral public policy astray. Available at SSRN 4046264.

opponents of concerted systemic action such as regulation and taxation. We illustrate our argument, in depth, with the examples of climate change, obesity, savings for retirement, and pollution from plastic waste, and more briefly for six other policy problems. We argue that behavioral and social scientists who focus on i-level change should consider the secondary effects that their research can have on s-level changes. In addition, more social and behavioral scientists should use their skills and insights to develop and implement value-creating system level change.

This is, in a sense, a continuation of yesterday’s post. The point of this paper, the one we’re discussing today is to say that we, as a society, have begun to think of i-frame solutions as substituting for s-frame solutions, rather than complementing them. And that, the authors say, is quite problematic.

Problematic for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is the fact that an excessive dependence on i-frame solutions can make it less likely that complementary s-frame solutions will be adopted. In addition, i-frame solutions in and of themselves tend to have either no, or close to no effects.

Worse, the idea that i-frame solutions may be enough in and of themselves, the authors say, is an idea that may well have been pushed on us by corporations:

Readers who see waste as a matter of individual responsibility may be surprised, as we were, to discover that this i-frame perspective can be traced to the influence of industry. Consider, for example, the ‘Keep America Beautiful’ PR campaign that baby-boomers will have had drilled into them, including the highly successful ‘Crying Indian’ ad – both about how individuals have a duty to pick up cans and bottles (Mann, 2021: 52-60). In the ad, an actor in Native American dress paddles a birch bark canoe on water that becomes increasingly polluted, pulls his boat ashore and walks toward a bustling freeway where a passenger hurls a paper bag out a car window. The ad concludes with an encapsulation of the i-frame perspective “People start pollution. People can stop it.” The ad, and the “Keep America Beautiful” campaign, which began in the 1950s and remains ubiquitous 70 years later, was actually the product of beverage and packaging corporations such as the American Can Co. and the Owens-Illinois Glass Co., later joined by corporations such as Coca-Cola and Dixie Cup.

Chater, N., & Loewenstein, G. (2022). The i-frame and the s-frame: How focusing on the individual-level solutions has led behavioral public policy astray. Available at SSRN 4046264.

Here’s the video:

Again, you may or may not agree that it is ‘big bad evil’ corporations that have been pushing these i-frame solutions upon us, and I myself tend to fall (surprise, surprise) somewhere in the middle. But I think it makes sense to think about whether one should exclusively push for i-frame solutions or think about some mixture of the two.

The paper covers much more ground across a very broad spectrum of topics, including healthcare and education, and I would strongly encourage you to read the whole paper. The point that I personally have taken away is a point that I am not entirely unfamiliar with – but it remains a point worth reiterating – that behavioral economics is a complement. Or as yesterday’s post puts it, it is the icing on the cake, not the cake itself.

For a change, I’ll quote the conclusion, but disagree with it:

Although today we see s-frame interventions as the path forward for behavioral public policy,

Chater, N., & Loewenstein, G. (2022). The i-frame and the s-frame: How focusing on the individual-level solutions has led behavioral public policy astray. Available at SSRN 4046264.

we, and many other behavioral scientists, previously had a very different picture in mind: that,

even where s-frame reform was required, a focus on additional i-frame interventions could only

help. But if the right s-frame solutions were available but not implemented all along, it is likely

that behavioral scientists’ enthusiasm for the i-frame has actively reduced attention to, and

support for, systemic reform, as corporations interested in blocking change intend. We have been

unwitting accomplices to forces opposed to helping create a better society.

The reasons I disagree with it?

- I honestly think behavioral economics has done more good than harm. I agree that the field may well have become a little overrated in the recent past, but on the whole, I think it to still be A Good Thing.

- I don’t think i-frame solutions have been (unwitting or otherwise) accomplices in the move to downplay s-frame solutions. Nor do I think that corporations have as nefarious a role to play as this paper seems to suggest. Don’t get me wrong: I don’t think corporations are ‘good’, but nor do I think they’re ‘bad’. The people who run them respond to their perceived incentives, just like you and I do.

But all that being said, a paper that introspects deeply about a topic that the authors care about as much as Loewenstein and Chater do is a wonderful one to read, and I strongly encourage you to do so.