Let’s say you’re a student who is going to start learning economics in the coming semester (starting July 2023). Let’s assume that you’ve never learnt economics in a classroom before, save for a brief introduction to it in high school. If you chose to learn from an LLM instead, how should you go about it?

Leave aside for the moment the question of whether you should be doing so or not. The question I seek to answer over many blog posts is whether you can do so or not. Whether or not this is a good idea for you depends in part on my abilities to add to the value that an LLM generates for you from such a course. And once these thirty (yes, thirty) blog posts are written out, I’ll write about my thoughts about whether a student still needs me in a classroom or not.

My current thinking is that I would still be needed. How much of this is hope, and how much dispassionate analysis is difficult to say right now. For that reason, I would like to tackle this problem at the end of this exercise. For the moment, I want to focus on helping you learn economics by teaching you how to learn it yourself, without the need for a human teacher (online or offline).

In each post, I’ll give you a series of prompts for that particular class. I will not always give you the output of these prompts – feel free to run them as they are, word for word, or tweak them as per your likes, fancies and hobbies.

My motivation in this series is twofold. One, to find out for myself just how much better ChatGPT is than me at teaching you principles of economics. Second, to help all of you realize that you ought to hold all your professors (myself included!) to a higher standard in the coming year. We have to do a better job than AI alone can, along all dimensions – let’s find out if we can.

Buckle up, here we go.

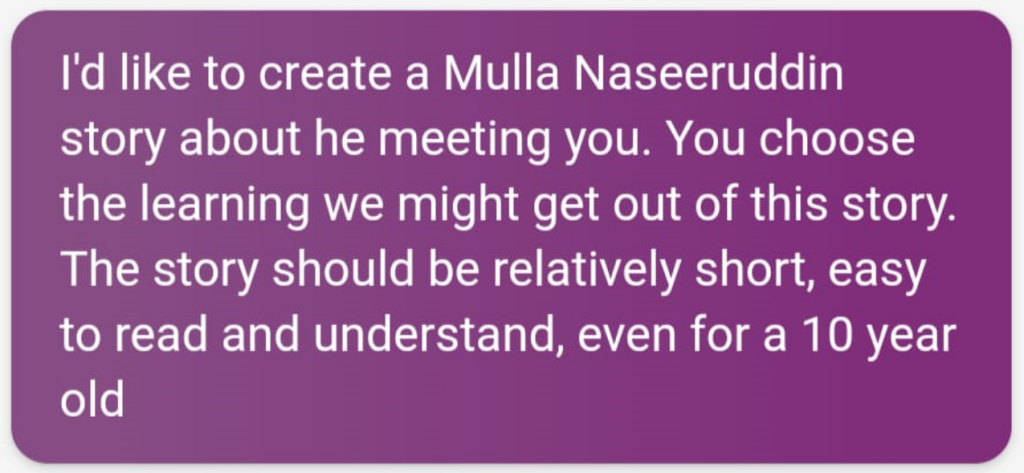

Here’s my first prompt:

Remember, LLM’s work best when you give really detailed prompts. Note the following:

- I began by giving some information about myself – my limitations as regards economics, where in the world I come from, and what my interests/hobbies/passions are.

- I specified what I’m looking to learn from the LLM.

- I specified the quantum of output required (thirty classes).

- I specified how broad the output should be.

- I specified how I would like the answer to be customized for me

- I would like to learn about economics by relating it to what I like to read about in any case (use examples from the Mahabharata)

- I would like to learn about economics by relating it to real life situations.

- It is amazing to me, regardless of how many times I experience it, that it “gets” what I really mean in spite of having phrased my question using really bad grammar.

- The specific examples aren’t the point, the idea is the point. Learn calculus by relating it to mandala art, for example. Learn history by relating it to dance forms. Learn geography by relating it to food from different parts of the world. A teacher in a classroom cannot possibly do this for all the students, because of the size of the class, and because a teacher cannot possibly know your hobby in as much detail as you can. Make good use of AI!

- Should the examples from the Mahabharata be chosen for how prominent the examples were in the text, or should they be chosen for their relevance to economics? My preference is for the latter, and I made sure the LLM knows this. Ditto for the real life examples.

- I ended with a meta-prompt, that will stay true for the next thirty (or more questions) – ask if I need to learn more, and only then proceed with the next class.

Should you copy this prompt, word for word? Of course not! For one, you may not want to learn economics, but rather a different subject. The underlying principles still holds. You may not like to read about the Mahabharata, for another. You may want only ten lectures, not thirty. Or you may want two hundred! Feel free to tweak the prompt to suit your requirements, but it helps to “get” how to go about thinking about the structure of the prompts. That’s the point.

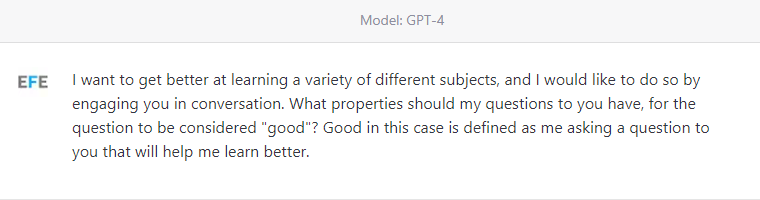

I took a look at the outline of the thirty course lecture series it prepared for me, and it was not bad at all. But I had a follow-up request:

Now, you might think that you need to know economics in order to judge the output, and tweak your request. And sure, you’re right that it will help. But regardless, even if you cannot judge the quality of the output, surely you know enough about what and how you want to learn. My apologies for going all meta on you, but if you don’t know enough about the supply side of the market, surely you know what you would like as a consumer – at least in part. So feel free to help the LLM become a better teacher by telling it more about you.

It went ahead and gave me the refined output, and also the broad contours of the first class. Here are the broad contours of the first class:

Again, note that I am quite excited about how this class is shaping up, because if economics is, indeed, the study of how to get the most out of life, Arjuna’s choice to fight in the Kurukshetra war is an awesome way to get some really thought-provoking questions in for discussion. But this may not be your cup of tea – so feel free to brew your own cuppa of econ, by customizing it to what you like the most (Avengers? Cricket? RRR? Bharatnatyam? Junk food? Anime? Go for it!)

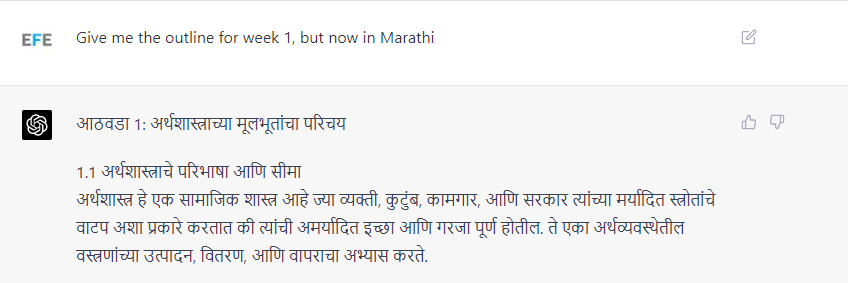

I did have follow-up questions:

And based upon its answer to this prompt, I had yet another clarificatory question:

Note that your conversation will be (I would go so far as to say should be) different. You will have different questions, different prompts, different things that make you curious. And that’s not just fine, that is the whole point. Depending on how carefully you read its output, and depending on how probing and detailed your questions are, you can keep just this first class going for a long, long time. How long? That’s up to you!

Here are two examples:

You can, of course, ask it to answer any (or all) of these five questions. Ask it to create ten (or twenty, or a hundred) instead – and as a student, assume that this is how us professors might well be “coming up” with questions for your tests, assignments and exams.

Here are more, and note how they get wilder (more random?) with each passing question:

In each of these cases, you don’t have to have trust in, or agree with, the answer given by the LLM. Treat the output as a way to get you to think more deeply, to challenge what has been said, to verify that the answers are correct, and to have further discussions with your peers and with your (human) teachers, whoever they may be.

Note to myself (and to other teachers of an introductory course about the principles of economics):

- How can we do a better job than this in the classroom…

- Without using AI (we’re substitutes)?

- By using AI (we’re complements)?

- What is missing from the LLM’s output (this is assuming you’ve tried these prompts or their variants)?

- What stops us from recommending that students do this in class on their own devices, and we observe, nudge and discuss some of the more interesting output with everybody? That is, how does teaching change in the coming semester?

Feedback is always welcome, but in the case of the next thirty posts, I think it is especially important. So please, do let me know what you think!