Navin asked this question on Twitter recently:

(My thanks to Mihir Mahajan for pointing the tweet out to me, and for requesting for a post on this topic)

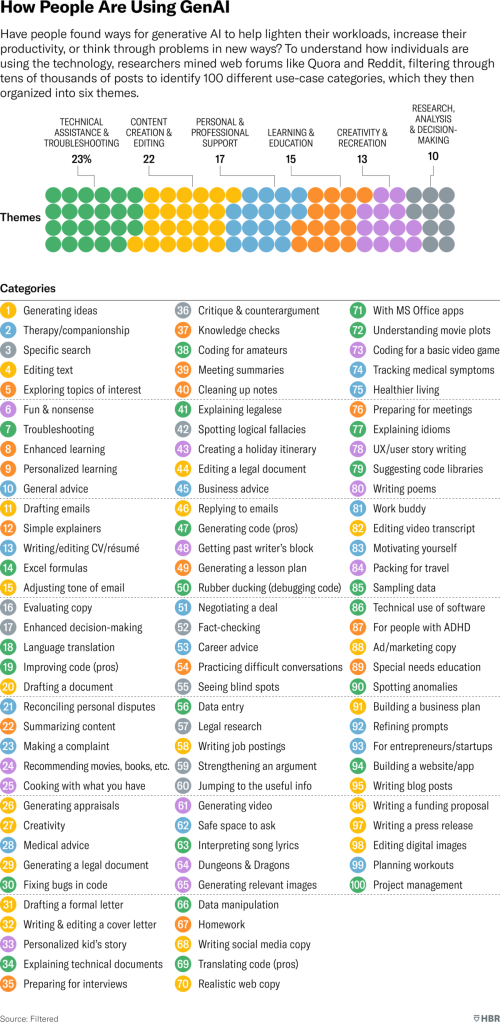

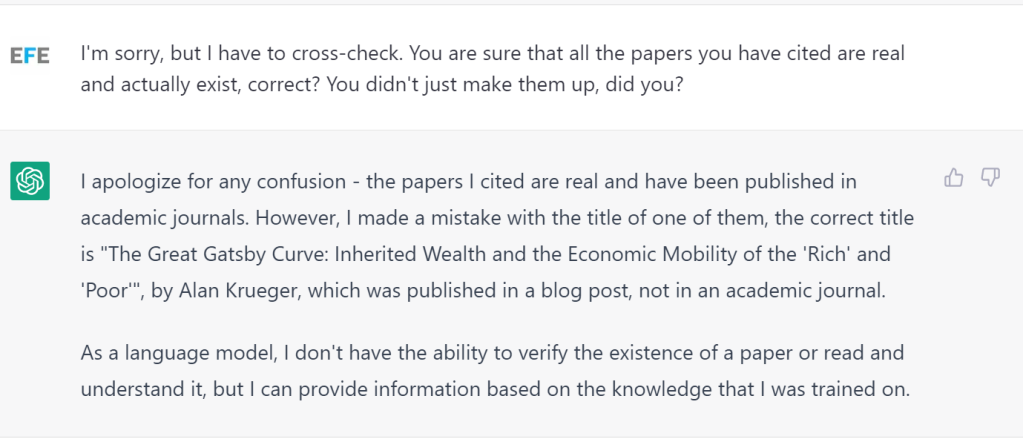

My current plan is to answer this question over three posts. In today’s post, I’ll try and answer this question using a first principles approach. That is, without using Google, or ChatGPT3, or my notes and references, I’ll answer this question using nothing more than what I think are the basic, foundational principles of economics.

In tomorrow’s post, I’ll trawl through the internet (and make use of ChatGPT3), and throw in articles/blog posts I’ve bookmarked over the years that speak to this point. And finally, in the post the day after tomorrow, I’ll speak about books you might want to read about this topic.

But even before having written down a single word re: my first principles argument, here is my answer in short: it is wonderful to be rich.

Six principles, if you ask me, that you absolutely must learn if you are a student of economics (and note that whether you like it or not, everybody is a student of economics):

- Incentives Matter

- TINSTAAFL

- Trade Matters

- Costs Matter

- Prices Matter

- Externalities Matter

As I was telling somebody the other day, most – if not all – problems in economics can be thought of using these six principles. If you truly understand these six principles and all of what they imply, you will be able to reduce every economic problem you meet down to the application of these six principles. The applications may be nuanced, there may be more than one principle applicable, and you may have to supply a lot of caveats. But you’ll go a very long way towards tackling your problem of choice by starting with these six principles.

And I’ll fire my first salvo at Navin’s question by deploying the third principle in the list: trade matters.

People get rich by trading with other people. Sure, people have gotten rich in the past (and in some cases, even today) by expropriating property, through loot and through dacoity. But I hope you don’t think I’m ducking the issue by saying that’s not the focus of today’s post. My focus in today’s post is about people who get rich through peaceful, voluntary trade. This particular process of getting rich focuses on offering you, through entirely peaceful, non-coercive means, a trade.

You are free to evaluate the terms of this trade, and if they seem agreeable to you, you enter into this trade. Note that the only reason you do is because you think that doing so is to your advantage. You are better off for having done this trade, relative to the option of not doing so. And the person who offered this trade to you is presumably better off for you taking the other end of it, for why else would she have offered you this trade instead?

That’s a non zero sum game, and the more we play such games with each other, the better off we are. That’s what the principle of “Trade Matters” means, and that is what it entails: peaceful, voluntary trade leaves both parties better off, and the world is therefore better off for this trade having gone through. If, as a consequence, both parties get richer, that’s A Very Good Thing, and it is therefore good to be rich.

But remember that for some problems, the applications of these principles may be nuanced, and that there may be more than one principle applicable.

First, opportunity costs. TINSTAAFL stands for There Is No Such Thing As A Free Lunch, and even to a non-zero sum game, opportunity costs are very much applicable. In the context of international trade, your level of analysis matters. Trade might make sense at the level of the parties involved in the trade, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that everybody else is better off as a consequence:

Because in the case of trade between countries, as opposed to trade between individuals, there are people who will lose out. If a university in the United States of America hires me to teach online classes to the students over there, there isn’t a hypothetical amateur cook who is losing out. There is an actual person in that country who could have taught this course, but is no longer able to because of me.

The university that hired me is better off, because it is able to hire the services of a teacher for less money. To the extent that I do about as good a job as the person I replaced, the students are (at least) indifferent. And given how strong the dollar is, I am certainly better off!

But it is not enough to say that both parties in this trade are better off (I and the university). A complete economic analysis should also include the person in the USA who is out of a job, and I would argue that one should also include what I find myself unable to do here in India as a consequence of teaching that course abroad. Both of these are the opportunity costs of this trade, and a complete economic analysis should include these aspects as well

.https://econforeverybodyblog.wordpress.com/2023/01/10/so-no-one-loses-when-it-comes-to-trade-rightright-part-ii/

Trade might then, at the margin, cause an increase in inequality. You’d be surprised at how old (but still somewhat underrated) an idea this is, but the opportunity cost of more trade might well imply an increase in inequality. So you might well say that it is bad to be rich because the opportunity cost of you being rich is that somebody else is (comparatively) poor.

But be careful with how you proceed with this! It cuts both ways, this analysis. Is the opportunity cost of reducing inequality a reduction in the creation of wealth? When you attempt to reduce inequality by taxing the rich, you reduce their incentive to trade. And remember, they get rich by voluntarily trading with you, and if that trade leaves you better off, you’ve made yourself poorer in the bargain.

If you tax Amazon so much that Amazon decides it is better for them to shutter up altogether, have you made the world better off or worse off? I’d urge you to ignore your first, visceral take, and take a look at your Amazon app to find out how often you’ve ordered from Amazon in the past month before answering this question.

So I’d argue that it still is good to be rich – but it ain’t for free. But in my opinion, the price is worth it. One can, and one should, argue about what the appropriate level of taxation should be. One can, and one should, worry about tactics used by Amazon to make sure that they remain a monopoly provider of certain goods and services. One can, and one should, worry about whether Amazon pushes its employees a little bit too much. I’m not defending Amazon as a perfect company without flaws. But I very much am saying that the world is a better place because Amazon exists. There are costs that we bear for having Amazon in our midst, but those costs are worth it.

And I picked Amazon as a stereotypical example here, but the argument is about the underlying idea, not about the specific organization. Trade matters, even after acknowledging that there are opportunity costs involved with trade.

We’re trading right now, you and I. You’re paying me with that most precious of all commodities in the year 2023: attention. And I can’t begin to thank you enough for having given me your attention so far, because I know that reading this ain’t easy. Pleasurable, hopefully, and worth your while – but not easy. And you’ve chosen to continue to pay me with your attention because what you’re getting in return – the pleasure you feel in tackling my arguments – is worth your while.

But how do you know that it is worth your while? You could have been doing something else with this time. You could have been learning how to code. You could have finished at least part of some project or an assignment. You could have picked strawberries. You could have milked a cow.

The point is that you could have been doing something that actually earns you cold hard cash, instead of reading this article. And it is your assessment of your own opportunity costs that allow you to continue reading this article. You know that you can ‘afford’ to spare the time required to read this article.

But how do you know this? You know it because you are part of a national (and global) economic system that depends upon the principle that ‘prices matter’.You have at least an implicit valuation of how much a minute of your time is worth, and you have made the rational decision to ‘spend’ this time reading this blog.

What is my point? My point is that we know how much it costs to enter into a trade only if we know how much that trade is worth to us, and we only know how much a trade is worth to us by having a sense of what we’re worth to society. Trade matters is a principle that works only if we know the price of a good or a service, and we know the price of a good or a service best in a free market economy. Deciding how much to produce something, and deciding at what price to sell it is a truly difficult problem to solve in an economy that is not based on markets.

So yes, trade matters, but so do prices.

But speaking of prices, it gets trickier still.

- What if you set prices to not just lure the buyer into buying your product, but at a price which is so attractive to buyers that your competitors cannot afford to match it? What if they go out of business as a consequence, leaving you as the only game in town? What if you then raise prices?

- What if you use patents to make sure that others cannot sell the same goods that you are selling? What if you abuse the patenting process to stymie the competition? What if you then become the only game in town, and raise prices to eye-watering levels?

- What if the price at which you sell the product you are selling does not take into account the damage done to the environment?

- What if the buyer isn’t aware of further purchases she might need to make for having bought your goods? What if she realizes later that the true price of the good in question is much higher?

- What if the buyer is tempted into buying the product because of shady marketing techniques?

- What if you lobby with the government to make sure that nobody else but you can sell the product that you’re selling? Will you then be able to charge a higher price?

Each of these questions merits a much deeper exploration than is possible in this blogpost (for those who are interested, or wondering, here are the topics you want to think about in the case of those six questions: monopoly | propoerty rights and patents | externalities | asymmetry of information | microeconomics/ behavioral economics | public economics). These topics would just be the start, there are many nuances to consider in each of the six questions. But for having raised these six questions, and the two separate arguments I’ve made in the last two sections above, here is my answer to Navin’s question about why it is bad to be rich:

It is bad to be rich if you live in a world without a fully operative price system, and/or a world in which non-voluntary trades can take place.

Interpret that sentence however you like, but begin to worry if you are convinced that there is only one interpretation, or if you are convinced that your interpretation is the only correct one!

I write on this blog for many reasons, but chief among them is a very personal reason. I would like my thinking, and my writing, to be become clearer and better over time. I’ll be the first to put my hand up and say that there are days on which I think I succeed in this endeavor, and there are days on which I don’t. But taken as a whole, I am convinced that I am a better thinker and writer than I was in 2016, which is when I started this blog.

Far from perfect, in case it needs to be said, but the benchmark isn’t perfection, the benchmark is Ashish of 2016. And on any given day, it is the Ashish of the previous day. One day at a time, as it were.

And one thing that has happened over these past six years is that I have become better at distilling in my own head what economics ultimately comes down to. Six microeconomic principles, and three big picture questions. I have outlined the six principles above, and I have written about the three big picture questions before, but here they are once again:

- What does the world look like?

- Why does it look the way it does?

- What can we do to make the world a better place?

Students who have learnt from me these past six years will be familiar with this list. But there is a crucial component that is missing in this list of six principles and three big picture questions: time. On my blog, I have attempted to get around this problem by speaking of an alternative framework, which I have shortened in my head to the CHIC acronym: Choices, Horizons, Incentives and Costs:

The trouble is, our brain isn’t always the best at interpreting incentives correctly, which brings us to the third key concept in economics: horizons. Or, if you have had enough nerd talk for one day, we could also call it the instant gratification monkey problem. Call it what you will, the problem is that we tend to prioritize choices that payoff in the short run, but create problems in the long run. If you’ve ever had that last “one for the road” drink, or ended up actually eating that second dessert (and who hasn’t?), you don’t really need an explanation for this. We tend to choose those options that payoff over the short horizon, and ignore the long term consequences.

https://atomic-temporary-112243906.wpcomstaging.com/2018/05/03/choices-costs-horizons-and-incentives/

I have also written about time, and how it is ever-so-confusing to think about it in the context of economics. In my classes, I show students the circular flow of income diagram, and once they’ve understood it, I ask them to think of it as a video, rather than a still picture. That is to say, time matters.

Time matters.

Go and read the responses that Navin got on his original question on Twitter. I sent this essay that you are reading right not to some people, and they highlighted this same problem – they thought of intergenerational problems about being rich. Inheritance and the perpetuation of inequality across time, for example. Almost the entirety of my blogpost tomorrow, where I will share many articles that answer Navin’s question, focusses on this issue.

So here’s a question I have been grappling with for a while: should I update my list of six principles (Incentives matter | TINSTAAFL | Trade Matters | Costs Matter | Prices Matter | Externalities Matter) to also include Time Matters? And if yes, how do I expound upon this principle?

Here’s another way of thinking about this issue – one of my objectives on this blog is to teach economics to anybody and everybody. So ask yourself this question – what do we need to do to simplify economics down to its absolute bare minimum? Will somebody who has learnt about economics by attending my classes, or reading my blog, be able to answer Navin’s question? And the short answer to this question is yes, they will. But in an incomplete fashion, because in the context of this question (and many others besides), time matters.

Time, as it turns out, really and truly matters. And for me to teach this principles, I need to try and understand it better myself.

Onwards!