It might seem like a rather weird topic for a blog called Economics for Everybody to think about, but what explains the rise, and the seemingly inevitable ascent to the Presidency of the USA, of Mr. Trump?

This blog post isn’t about the politics of Mr. Trump, endlessly fascinating a topic though it is. It is instead about an attempt at looking at the economic factors that caused this phenomenon to occur at all.

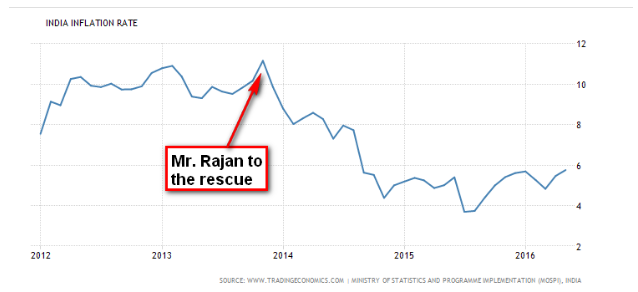

And one cause is related to this:

Of the jobs lost during the recession, about 60 percent of them were in what are called “mid-wage” occupations. What about the jobs added since the end of the recession? Seventy-three percent of them have been in lower-wage occupations, defined as $13.52 an hour or less.

That is pulled from a book written by Tyler Cowen, called Average is Over. Read the whole book, it is worth the price of admission. But the trend that is highlighted in this book is the trend that is causing the rise and rise of Mr. Trump.

One, there are likely to be fewer jobs for all of us in the future. Two, those jobs that do exist are not going to pay very well at the bottom of the pyramid. One shouldn’t describe a book in two sentences, but that’s the quick summary of Average is Over.

Here’s the thing, though: machines don’t vote. People do. And who do you think those seventy-three percent in the block-quote above are going to vote for? For the guy who promises to cure their problems by – well, by curing their problems.

Mr. Trump’s solutions might not win him an academic degree in economics, but that’s not the race he’s running. The race he’s running is being judged by the people who have mostly lost in this era of globalization, and according to some of them, he’s doing just fine. If this “disenchanted” group turns out to be large enough, and motivated enough, Mr. Trump stands a very real chance of becoming President Trump by year end.

The disenchanted workers of the globalization era is not a new idea, far from it. And there is a lot more to the idea than what has been written here. The reason I’m writing about it now, and the reason I’m highlighting this one factor above all else, is because old theories are beginning to receive fresh validation, and that makes it an exciting time to be an analyst.

Being a global citizen right now, on the other hand, might well raise the demand for blood pressure pills.