I had (and have) sympathy for Navin, but I have to confess that I did enjoy reading this tweet, because it is very much a teachable moment:

Why is this a teachable moment?

Because firms have an incentive to make it as difficult for you to “leave”. They make it as easy, painless and frictionless as possible for you to “join”, and they make it as difficult, painful and, well, friction-full as possible for you to leave.

Here’s Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein on this phenomena:

Perhaps the most basic principle of good choice architecture is our mantra: make it easy. If you want to encourage some behaviour, figure out why people aren’t doing it already, and eliminate the barriers at a standing in their way. If you want people to obtain a driver’s licence or get vaccinated, make it simple for them, above all by increasing convenience.

Nudge, by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, Chapter 8, pp 151, Kindle Edition

Of course this principle has an obvious corollary: if you want to discourage some behaviour, make it harder by creating barriers. If you want to make it harder for people to vote, forbid voting by mail and early voting, and reduce the number of polling stations (and place them far away from public transportation stops). While you’re at it, try to make people spend hours in line before they can vote. If you don’t want people to immigrate to your country, make them fill out a lot of forms and wait for months for good news in the mail (not by email), and punish them for answering even a single question incorrectly. If you want to discourage poor people from getting economic benefits, require them to navigate a baffling website and to answer a large number of questions (including some that few people can easily understand).

And they have a term for it too – sludge:

Any aspect of choice architecture consisting of friction that makes it harder for people to obtain an outcome that will make them better off (by their own lights).

Does not getting spam mails in his inbox make Navin better off, by his own lights?

Yes, of course!

Does the design of the unsubscribe (I’m being generous here) form add friction to the process of Navin obtaining this outcome?

Yes, of course!

That’s sludge in action.

And once you “see” it, you begin to spot it everywhere. Newspapers and magazines make it difficult for you to cancel your online subscriptions and banks make it difficult for you to file a complaint with the banking ombudsman, to give you just two examples. I’m sure you can think of many more from your own life, and Chapter 8 of the book Nudge has many, many other examples. Please read the whole chapter (and if you’re willing to humor me, the whole book).

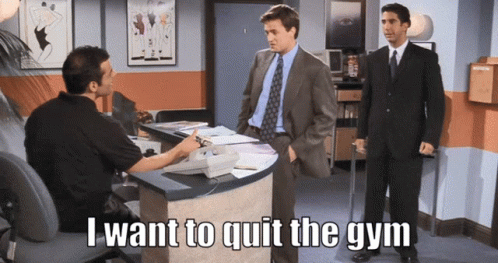

And finally, this might resonate with people of a certain age (or maybe, even now, all ages?):

If you have the Monday blues, and now have an irresistible urge to drop everything else and watch the whole episode instead, it’s S04E04.

You’re welcome.