“Here is a game called buzkashi that is played only in Afghanistan and the central Asian steppe. It involves men on horseback competing to snatch a goat carcass off the ground and carry it to each of two designated posts while the other players, riding alongside at full gallop, fight to wrest the goat carcass away. The men play as individuals, each for his own glory. There are no teams. There is no set number of players. The distance between the posts is arbitrary. The field of play has no boundaries or chalk marks. No referee rides alongside to whistle plays dead and none is needed, for there are no fouls. The game is governed and regulated by its own traditions, by the social context and its customs, and by the implicit understandings among the players. If you need the protection of an official rule book, you shouldn’t be playing. Two hundred years ago, buzkashi offered an apt metaphor for Afghan society. The major theme of the country’s history since then has been a contention about whether and how to impose rules on the buzkashi of Afghan society.”

That is an excerpt from an excerpt – the book is called Games Without Rules, and the author, Tamim Ansary, has written a very readable book indeed about the last two centuries or so of Afghanistan’s history.

It has customs, and it has traditions, but it doesn’t have rules, and good luck trying to impose them. The British tried (thrice) as did the Russians and now the Americans, but Afghanistan has proven to be the better of all of them.

Let’s begin with the Russians: why did they invade?

One day in October 1979, an American diplomat named Archer K. Blood arrived at Afghanistan’s government headquarters, summoned by the new president, whose ousted predecessor had just been smothered to death with a pillow.

While the Kabul government was a client of the Soviet Union, the new president, Hafizullah Amin, had something else in mind. “I think he wants an improvement in U.S.-Afghan relations,” Mr. Blood wrote in a cable back to Washington. It was possible, he added, that Mr. Amin wanted “a long-range hedge against over-dependence on the Soviet Union.”

Pete Baker in the NYT speaks of recently made available archival history, which essentially reconfirms what seems to have been the popular view all along: the USSR could not afford to let Afghanistan slip away from the Communist world, no matter the cost. And as Prisoners of Geography makes clear, and the NYT article mentions, there was always the tantalizing dream of accessing the Indian Ocean.

By the way, somebody should dig deeper into Archer K. Blood, and maybe write a book about him. There’s one already, but that’s a story for another day.

Well, if the USSR invaded, the USA had to be around, and of course it was:

The supplying of billions of dollars in arms to the Afghan mujahideen militants was one of the CIA’s longest and most expensive covert operations. The CIA provided assistance to the fundamentalist insurgents through the Pakistani secret services, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), in a program called Operation Cyclone. At least 3 billion in U.S. dollars were funneled into the country to train and equip troops with weapons. Together with similar programs by Saudi Arabia, Britain’s MI6 and SAS, Egypt, Iran, and the People’s Republic of China, the arms included FIM-43 Redeye, shoulder-fired, antiaircraft weapons that they used against Soviet helicopters. Pakistan’s secret service, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), was used as an intermediary for most of these activities to disguise the sources of support for the resistance.

But if you are interested in the how, rather than the what – and if you are interested in public choice – then do read this review, and do watch the movie. Charlie Wilson’s War is a great, great yarn.

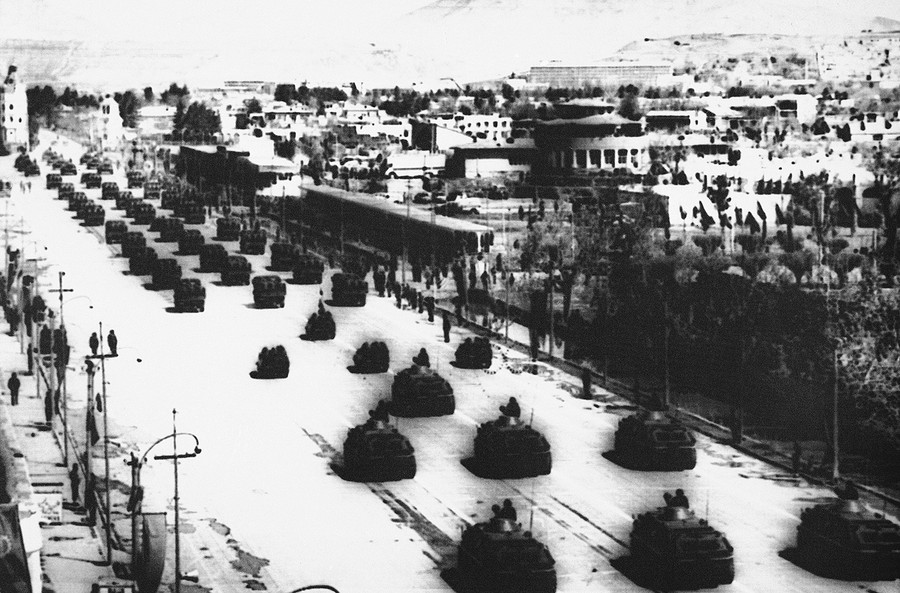

Powerful photographs that hint at what the chaos of those nine years must have been like, from the Atlantic.

And finally, from the Guardian comes an article that seeks to give a different take on “ten myths” about Afghanistan, including the glorification of Charlie Wilson:

This myth of the 1980s was given new life by George Crile’s 2003 book Charlie Wilson’s War and the 2007 film of the same name, starring Tom Hanks as the loud-mouthed congressman from Texas. Both book and movie claim that Wilson turned the tide of the war by persuading Ronald Reagan to supply the mujahideen with shoulder-fired missiles that could shoot down helicopters. The Stingers certainly forced a shift in Soviet tactics. Helicopter crews switched their operations to night raids since the mujahideen had no night-vision equipment. Pilots made bombing runs at greater height, thereby diminishing the accuracy of the attacks, but the rate of Soviet and Afghan aircraft losses did not change significantly from what it was in the first six years of the war.