- Half the width of the footpath is for businesses, and this is formally/informally understood. The reason for the “/” is that in some cases, there is a white line running along the length of the footpath that kinda sorta officially sets the boundary.

- The other half is not necessarily always for walking, it can be used for parking too. In this sense, walking in Hanoi was very similar to walking in India. Some cafes actually have little wooden blocks that are kept adjacent to the footbath, so that bikes can be pushed onto the footpath. Can be used by paying customers of the cafe only, of course.

- Traffic is as chaotic as India, but pedestrians assume that the vehicles will stop for them (and they do). Here, of course, it is the other way around.

- Coffee rules. I approve. We stayed next to a lake, and sitting on one of those small chairs and sipping on black coffee is a wonderful way to spend an hour or so.

- I couldn’t help but wonder if the word “banh” comes from “pain” in French, which means bread. But apparently not.

- The drop-off in quality of visible infrastructure is as startling as it is in India. You know how the areas around where the bigwigs stay and immediately outside the airport in your city are much better than the neighbourhoods where aam janta stays? Hanoi is exactly like that, but marginally cleaner.

- You can’t go wrong with the food, and in more ways than one. Almost all of the stalls and shops along the main roads and with fronts opening up on the streets are tourist friendly, and the food is excellent.

- When I say tourist friendly, I don’t mean to say the rest of the city is not friendly. I mean the dishes are tourist friendly. Which is why a food tour is recommended – because you’ll never get to even see some of the more “hidden” places. If you’re feeling adventurous, try the balut. I did, but couldn’t manage more than one bite.

- There is a lot more to Vietnamese cuisine than just the pho and the banh mi, and the best way to learn about it is to walk, mostly through the old part of town. Walking is also the best way to experience the city.

- The higher the rating for a place on Google Maps, and the more the number of ratings, the more likely it is that the place is a favorite with tourists. This is a good example, but there are many such places. This will be good food, but it won’t be truly Vietnamese. It will be a somewhat decent version of heavily touristified Vietnamese cuisine.

- But when you’re traveling with a ten year old, that may not be a bad thing. What are you optimizing for?

- But while walking to your restaurant of choice, feel free to stop and try as much of the food from the street side shops as you possibly can. Surprises abound on virtually every corner.

- I observed shop-owners and friends sit down for a meal in their shops, or in front of their shops, on more than one occasion. A sense of community is palpable, and if not a meal, often a cigarette and a coffee, or a beer. Wonderful.

- Staring at your phones isn’t a thing if you are in charge of a streetside shop. At least, isn’t as much of a thing as it is in India. Note that these things are hard to quantify!

- Don’t order a dish for yourself in restaurants. Order, instead, lots of small dishes and share.

- The food is not spicy. The flavors are, as a rule, more subtle than in, say, Thai cuisine, or Malay cuisine.

- Our food tour guide told us that cats are considered unlucky in Vietnam because the meowing of cats sounds similar to the word “poor” in Vietnamese. Huh.

- I was hoping for better bakery products.

- Don’t waste a meal by going into a truly fancy place. If your time is limited, have every single meal in as many local places as possible.

- The Vietnamese National Museum of Fine Arts is well worth a visit, and you could easily spend half a day there, if not more. The ground floor and the third floor were my favorites.

- Bottomline: heavily recommended!

Tag: art

What Are You Optimizing For, Weird Art Edition

A Danish artist who pocketed large sums of money lent to him by a museum – and submitted empty frames as his artwork – has been ordered by a court to repay the funds.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/sep/18/danish-artist-jens-haaning-empty-frames-ordered-repay

So begins an article in the Guardian (h/t John Burn-Murdoch on Twitter). It is a short article, won’t take more than a couple of minutes to read it. But it will take you a fair bit of time and effort to understand its implications in their entirety.

An artist called Jens Haaning was commissioned by the Kunsten Museum in Aalborg to recreate two earlier works by him. One of these was titled An Average Danish Annual Income. It simply displays krone notes in a canvas. Another work by the same artist is apparently pretty much the same idea, but using euro notes instead.

So this time around, the Kunsten Museum provided about 61k Euros, give or take, to recreate the work. The result?

But when staff unpacked the newly delivered works, they found two empty frames with the title Take the Money and Run.The museum put the new artworks on display, but when Haaning declined to return the money, it took legal action.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/sep/18/danish-artist-jens-haaning-empty-frames-ordered-repay

Well, is it a crime or not? Did he create a work of art or not? What does the law say, and what does economic theory say?

Here’s my understanding from an economic perspective:

- Yes, he created a work of art. One may not like it, one may not approve of it, but it is there all right.

- Was he obligated to use the currency notes that had been supplied? My take is that he wasn’t, unless this was explicitly specified in the contract. I have of course not seen the contract, but I found this interesting: “The work is that I have taken their money. It’s not theft. It is breach of contract, and breach of contract is part of the work”.

- I find this interesting because the artist seems to be making the argument that even if the contract was explicit about using the supplied currency notes in the artwork, his interpretation of the commissioned project involved breaching the contract. What is more important when it comes to a case like this? The legal interpretation of the contract or the (artistic) interpretation of the same document by the artist?

- As regards that last question in pt. 3, how should the artist think about this? How should a lawyer think about this when on the prosecuting side? How should a lawyer think about this when on the side of the defense? How should an economist think about this? How do you think about this?

- The article ends with this (deeply troubling for me) quote: “I encourage other people who have working conditions as miserable as mine to do the same. If they’re sitting in some shitty job and not getting paid, and are actually being asked to pay money to go to work, then grab what you can and beat it”

- “Working conditions as miserable as mine”? Who decides? On what basis? By what benchmark? Is the benchmark a universal one, or does it change by country? Or by some other variable(s)? How do we decide?

- Does this apply to all creative endeavors? What if I don’t teach Principles of Economics well, or at all? Do students learn better when they are forced to learn on their own? If yes, am I actually being a good teacher by refusing to teach?

- Writing contracts out explicitly matters. Institutions matter. Repeated games in game theory matter.

- And dare I say, ethics matter.

Art Valuation and Football

Yes, I know because I buy them. [laughs] I used to be annoyed by this, and now I think it’s the most delightful thing in the world because there’s all this loose money sloshing around, and so-called contemporary art is like this sponge that just absorbs all of it. There’s none left. Some of the things I buy, I am the only bidder. I get it for the reserve price. No one else in the world wants it, or even knows that it’s being sold, so I am delighted about this. The answer to your question, which artists are undervalued? Essentially, all good artists. The very, very, very famous artists, artists famous enough for Saudis to have heard of them — Leonardo, I would say, is probably not undervalued. But except for the artists who are household names — every elementary school student knows their names — they’re all undervalued.

https://conversationswithtyler.com/episodes/paul-graham/

As with almost all episodes in Conversations with Tyler, this one too is worth listening to in its entirety. I’m only halfway through, but I particularly enjoyed the excerpt I’ve quoted above.

Lots of reasons for me to have liked it – I know next to nothing about art, I enjoy thinking about what is underrated (and therefore undervalued), and I enjoy understanding more about how different markets work.

But also, I like watching and reading about football.

There’s been some seriously big players who’ve made the move into the Saudi league in the past year or so, with the biggest name being Ronaldo, of course. And there’s been a lot of hand-wringing about it.

But you might want to think about the following points, as I have been:

- Have the valuations been unusually high for the players that made the move?

- Did the football clubs actually get a pretty good deal then?

- How should they go about using this money? The same way the Saudi league is snapping up players, or the way Paul Graham buys art?

- What is the framework that Paul Graham uses while

buyingthinking about art? Is the same framework applicable in other markets, and not just football? - Which other markets have the same phenomenon playing out right now (akin to the Saudis buying out the “big” names?)

- How should you think about selling in such a market?

- How should one think about regulating such a market?

- Should one think about regulating such a market?

- What does equilibrium even mean in such a market?

- With regard to that last question, over what time horizon?

I plan to have a conversation about these questions with ChatGPT, and then with some friends. If you like football, economics or best of all both, it might be a fun way to spend a couple of hours!

Art and Economics

For the last three years now, I’ve been teaching a course called Principles of Economics to the first year students of the undergraduate program at the Gokhale Institute, and of all the courses I’ve taught over the years, this one is closest to my heart, by far.

This is true for a variety of reasons: introducing a subject (any subject) is always fun, and even more so when you can see students fall in love with it. When students “get” the power of economics – when they learn to see the world as an economist does – it is so much fun to see them realize that there is so much work to be done in this field. And when they begin to apply these principles in their own lives, well, what more could one ask for?

But one reason that is perhaps a little bit underrated is that I get to teach folks who aren’t all that convinced that they should be studying economics in the first place. Some enroll in the course simply because they aren’t sure about what else to do. Some enroll in the course because their parents recommended that they do so. Still others see this as simply a place to spend three years before doing an MBA.

In such cases, the challenge is to teach economics by first latching on to something that they will enjoy learning about. Pick, that is to say, a topic that interests them, and help them understand how economics has a role to play in that topic. And slowly but surely, use that insight to have them then ask the obvious follow-up question: what else becomes clearer for having studied economics? And once they hit upon the answer themselves (“why, everything!”), well, we’re off to the races! (See pt. 4 in this blogpost)

And I’ve tried cricket, movies… and art.

There’s no end to the list of topics I could try this with, of course. Why are YouTube videos typically 10 minutes or so in length is a good question to ask, for example. Or you could talk about how Spotify is changing the way music is created. Or the economics of a bhurji stall. The list is endless.

But precisely because I know so very little about it, I have a soft spot for art.

And the book that started me off on my journey about learning more about economics through art is a lovely little book called Vermeer’s Hat, by Timothy Brook:

Vermeer’s Hat is a brilliant attempt to make us understand the reach and breadth of the first global age. Previously, all those pirates, explorers and merchant seamen seemed to belong to a separate world from the one inhabited by apple-cheeked Dutch girls smiling pensively at bowls of fruit. What Brook wants us to understand, by contrast, is that these domains, the local and the transnational, were intimately connected centuries before anyone came up with the world wide web. A start was made on this kind of work a decade or so ago with all those neat little books on a single commodity – spice, coffee and so on. But lacking the necessary context, they soon started to seem tiresome and slight, a mere listing of unlikely contingencies. What Brook shows is that with a driving intellectual design and a detailed understanding not just of “here” but “there” too, a history of commodities and the way they circulate is no mere novelty but a key to understanding the origins of our own modern age.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2008/aug/02/art.history

In the book, Timothy Brook speaks about eight of Vermeer’s paintings, and asks a deceptively simple question. What, he says, might we learn about trade in that era by looking at the objects within the paintings? Where did that fur hat come from in the Officer and the Laughing Girl? What about the map behind both of them? What does his painting of the view of Delft tell us about patterns of architecture, commodities trading and globalization more generally?

By the way, if you haven’t clicked on the links of those two paintings, please do take the time to do so. The website in question (essentialvermeer.com) is a lovely resource if you want to learn more about Vermeer, or for that matter about his techniques.

Imagine beginning a semester long course on international trade this way, rather than with a dull recitation of absolute and comparative advantage (I’m not saying the theories are dull, to be clear, but I am saying that the way they’re taught often is!). Economics can be brought alive by helping students realize that economics is about so much more than just one introductory textbook about the subject!

But the other reason for writing this post is that I think this would be a great way to learn more about India’s history (and her ancient patterns of trade) too! What if we tried to take a look at Indian art (paintings, murals, architecture, plays and so much more) and asked about the origins of objects within them, the style of depiction and the influences of different cultures, countries and creators? Both from an intra and an international perspective, my guess is that there would be much to learn and disseminate.

If you happen to know of YouTube channels/books/blogs/podcasts that cover this topic, please, do share!

Learn Economics By Looking At A Painting

It was the IPL yesterday, so why not art today?

Stare at this picture, and do so for a long time. If you are reading this on your phone, please take the time to switch to a laptop or even better, a desktop computer with a large screen. And just look at it, for as long as you like.

Here’s the description of this painting from Wikimedia:

On a table laid with a green table cloth and two linen damask serviettes are displayed: pewter plates with bread and a pewter dish with oysters, a glass of red wine, a glass of olive oil or a vinegar jug, a silver salt cellar, a rummer of white wine, a gilt silver cup, a pewter jug and a Berkemeyer laying on its side.

… which is fine as things go, but the NYTimes takes things to, as they say, another level in their Close Read series. I’ve linked to another one from this series more than a year ago, which is also worth your time. But this particular one, titled “A Messy Table, A Map of the World“, is worth an hour or more of your time.

In loving detail – and rarely must this phrase have been more appropriately used, Jason Farago takes us through the many messages, implications and nuances of this painting, and so much more besides.

I’ve noted below some points that stood out for me in terms of appreciating the painting better after having read the article (please note that I know nothing about art appreciation, so feel free to help me learn more):

- The reflection of the window-frame on the glass is remarkably well done, particularly on the wine glass, but also on the jug towards the right. The wine glass, by the way, is called a roemer, and the reason it has a knobbed stem is so that the glass is easier to grip after you’ve had a more than a couple of drinks.

- I wouldn’t have noticed it no matter how long I stared at it (but then again, I’m not very good at this), but directly below the half-hidden knife, on the edge of the white napkin is the artist’s signature, and the year in which the painting was created.

- The wall in front of which the table stands is drab by choice, so as to focus our eyes on the table itself.

- The lemon is mesmerizing. The realism that Heda manages is brilliant, and if you take a look at his other paintings, you will realize that it is a recurring motif.

- The texture of the bread in the foreground, the difference in the texture and the luster of the silver cup (or tazza) and the matte texture of the jug (or pewter) is remarkable.

I could go on, but I’ll leave you to both read the rest of the article, and figure out other details yourself.

But (surprise, surprise) what I enjoyed the most were the economic aspects.

- Learn more about where Heda was located, and why that mattered in terms of the commerce behind the creation of paintings such as these. Reflect on the section from the article that helps you understand why religious motifs are not to be seen in his works. While you are it, reflect on the fact that this is an artist known for the creation of a genre called late breakfasts. Who has the time to have late breakfasts, and what might that mean for the society that Heda lived in?

- Peperduur is a Dutch word, still in use today, that means expensive. It literally means “as expensive as pepper”. The peppercorns in the painting, by the way, are to be found in that little cone of paper towards the left of the painting.

- Where did the lemons come from back then? Were they imported? If so, from where? Under what conditions, treaties and laws? With what consequences? If you find yourself wanting to read more about this, I’m happy to recommend to you one of my favorite books about globalization: Vermeer’s Hat.

- Which other things came from which other parts of the world? The article tells us about gold, cinnamon, porcelain and pineapples that came from an island called Manaháhtaan. Where is this place, you ask? Well, near a place called New Amsterdam. And where is that, you wonder? Listen to this song, and read the lyrics.

- This is a painting that celebrates wealth: the fact that you were able to afford a spice that lives on today in a word that means expensive, that were able to afford to buy, eat and not finish something as expensive as oysters, that you were able to wash down the meal with beer and wine, that you were able to use only a bit of as expensive a fruit as a lemon, and that you could have a meal such as this for a late breakfast – all of this isn’t just telling the viewer a story. It is sending the viewer a message about what the Dutch people were when the painting was created. They were rich, and they wanted you to know it.

How they became rich, at what cost to the rest of the world, and with what consequences to themselves and the rest of the world are questions that you should ask after you stare at the painting… and then try and find out the answers.

There are many, many ways to learn economics, whether by watching the IPL or by learning about art appreciation – and a million other things in between. Being a student of economics is about so, so much more than the study of an economics textbook. That, if anything, is barely the start.

I hope you have as much fun learning about this painting as I did!

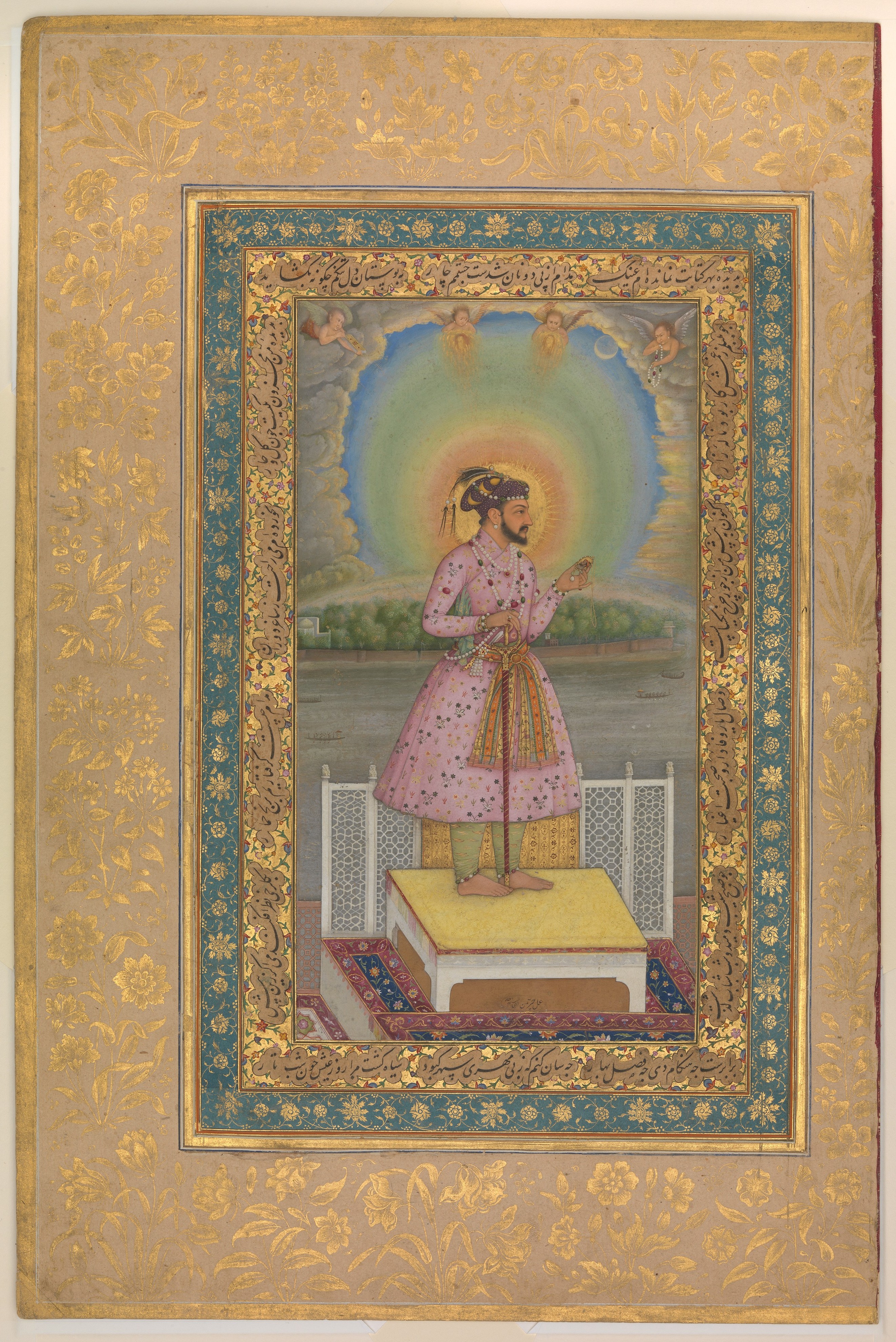

Chitarman’s “Shah Jahan on a Terrace, Holding a Pendant Set With His Portrait,”

You’ve probably seen this already, for it has been making the rounds on Twitter this past week. But just in case you haven’t, arm yourself with a cup (or two) of coffee, and spend about thirty minutes going over this feature.

It is beautifully done, and covers India, Persia, aspects of Christianity, Rembrandt(!), the advent of the British in India, Aurangzeb, the Taj Mahal and much more in a wonderfully informative package. Plus, personally speaking, I added two words to my vocabulary: anthomaniac, and lapidary.

ROW: Links for 31st July, 2019

- “There are things government could do if it were bold enough. How about a series of state-specific visas to foreigners, designed to encourage them to settle in Alaska and other underpopulated states? Alaska’s population could well rise to more than a million, and then the benefits of a good state university system would be more obvious, including for cultural assimilation. In fact, how about a plan to boost the population of Alaska to two or three million people? What would it take to get there?”

..

..

Especially read together with the last paragraph, this article is an excellent example of straight thinking – and one wonders where this might apply in India’s case?

..

.. - I’m breaking one of my own rules (but hey, that’s kind of the point of owning this blog), but here’s a short video about a tyre scultpure out of Nigeria.

..

.. - “Nonetheless, reading the testaments of people who’d come through a period of great uncertainty in the late 1920s and early 1930s, with the liberal order seemingly spent, it’s hard not to hear faint echoes in our current plight. As they do now, people then craved simple, emotional answers to complex economic and political problems.”

..

..

Learning more about the lives of ordinary people in the past is something I want to do more of. Germany and Germans when they realized the Russians were coming.

..

.. - “The official history of China’s economic reforms is rather more sanitized, but the memoirs of Gu Mu (谷牧), who was vice premier in the 1980s and in charge of foreign trade, do help show how export discipline was applied in the Communist bureaucratic system (see this post for some more interesting tidbits from Gu’s memoir).”

..

..

If there is one book that I would want a student of modern Asia to read, it would be Joe Studwell’s “How Asia Works”. This article begins by tipping its hat to that book, and speaks about how China instilled a sense of export discipline.

..

.. - A very long, mostly depressing article on an intellectual purge in Turkey.