The ability to exercise good judgment is the binding constraint in development is the title of Gulzar Natarajan’s blogpost on Oliver Kim’s essay, which we’ve covered earlier here.

Almost all of doing development is about making non-technical decisions (the technical ones are easier, have limited degrees of freedom, and mostly slot themselves into place). Such decisions are invariably an exercise of judgment by taking into consideration several factors, one of which is the technical aspect (or expert opinion). The most important requirement for the exercise of good judgment is experience or practical knowledge. In the language of quantitative science, it’s about having a rich repository of data points that one can draw on to process a decision.

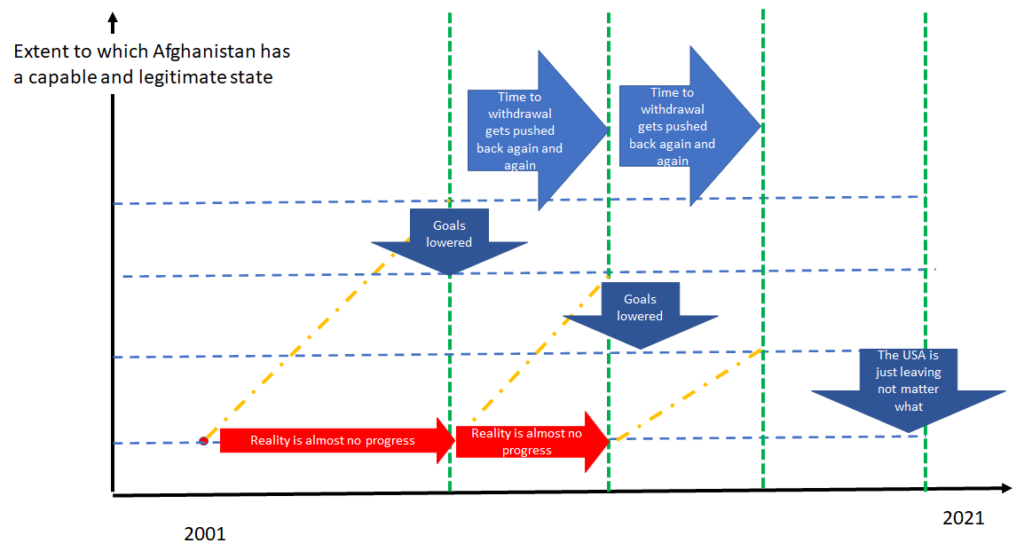

Source: https://urbanomics.substack.com/p/ability-to-exercise-good-judgment

This applies, Gulzar Natarajan says later on in the essay, to “industrial policy and promotion of industrial growth, macroeconomic policy and inflation targeting, and programs to improve student learning outcomes or skills, increase nutrition levels and health care outcomes, improve agricultural productivity, and so on”.

Let’s take one of these and think about it in slightly greater detail: health care outcomes. Let’s do this in the context of India. Answer these questions, for yourself:

- What is the best possible health care outcome you would wish for, in India’s context? Define it however you like – everybody should have excellent healthcare so long as they can pay for it is one option. Everybody should have excellent healthcare regardless of whether or not they can pay for it is another option. Everybody should have free healthcare until we reach a per capita income of x dollars (adjusted for inflation and purchasing power parity, if you prefer) is a third option. You can whistle up a million more, and feel free to let your imagination run wild. You get to define the best possible health care outcome for India – setting the standard is up to you.

- Microeconomists will call this the indifference curve, and ask you about the budget line. Mathematicians will call this the objective function, and ask you about the constraints. Humans will say “Haan woh sab to theek hai, magar bhaiya, kaise?”. This is the part where we encounter the bad news – what are you willing to give up in order to achieve your best possible outcome? Best possible health care outcome subject to we spending not more than 20% of our GDP on health might be a constraint you choose to apply, for example. Other people may start to froth at the mouth at the thought we spending 20% of our GDP on health, but you do you (for now). Reduce spending on defense, and pensions, and highways, and on education, you get to say (for now). In my little ivory tower, you get to say, I want India to focus on healthcare outcomes, and healthcare outcomes alone – and I’m ok spending x rupees on it. We get to not spend those x rupees elsewhere, of course – remember, opportunity costs are everywhere, including in imaginary ivory towers.

- Here’s another way to think about the same problem. You could also say, I’m optimizing not for healthcare outcomes in the short run, but for free markets. I’m not doing this because of my love for free markets per se, but because of my conviction that this path, and this path alone is the only way to deliver the best possible healthcare outcomes eventually. Sure there will be mistakes along the way, and sure some healthcare services will be denied to people who need it the most for now. But eventually, the market will correct all of these errors, and that in ways we simply cannot know right now. Why can we not know them right now? Well, because we are not omniscient. We don’t know what errors will crop up, and we don’t know what solutions will work best for whatever errors will crop up. If we did know this, we could have avoided those problems in the first place, no?

- There are, in other words, unseen consequences to Bastiatian solutions as well. That’s just a fancy way of saying there are opportunity costs everywhere, but let me make the point more explicitly: the opportunity cost of an immediate application of a completely free market solution to healthcare is poor health outcomes for at least some folks today. I might be wrong about this, so please, don’t hesitate to tell me the how and why of it.

For example, let’s say that government stops spending even a single rupee on healthcare (no CGHS, no PMJAY, no ESIC, no Jan Aushadhi, no government run hospitals, no PHC’s, no government run vaccination programmes, nothing) at 12 pm today. Will health markets be Utopian at 12.01 pm, or will they transition to Utopia eventually? How long is eventually? What problematic outcomes will occur along the way, and do we correct for them? How?

For example, we may learn that poor families in rural Jharkhand now do not have access to healthcare because all government intervention has stopped. Do we do something about this? If yes, what? If not, why? - This cuts both ways, of course.

For example, let’s say that government doubles its current expenditures on healthcare, at 12 pm. Will health markets be Utopian at 12.01 pm, or will they transition to Utopia eventually? How long is eventually? What problematic outcomes will occur along the way, and do we correct for them? How?

For example, we learn that corrupt practices when it comes to invoicing in procurement departments have gone up because government expenditure has gone up. Do we do something about this? If yes, why? If not, why? - Given your ideological bent of mind (and we all have one, learn to live with it), you have an urge to say “Ah hah, exactly!” and “Oh, c’mon!” to pts 4 and 5 – in that order. Or to pts 5 and 4 – in that order – it depends on what your ideology is. But if both of those things was what you ended up saying, that’s just you being bad at elementary economics, because there is no such thing as a free lunch, regardless of what your preferred solution is. You can have inequitable outcomes today and therefore a relatively more efficient outcome tomorrow, or you can have equitable outcomes today and therefore a relatively more inefficient outcome tomorrow.

Equity today and efficiency tomorrow is like those real estate ads offering you high returns and low risk – it doesn’t happen. - Which brings us back, in a very roundabout fashion, to the point that Gulzar Natarajan was making in his post. When he says that “it is not one decision, but a series of continuing, even interminable, decisions”, I interpret it as two different but very related things.

One, if you’ve chosen to optimize for equity today, you have to be explicit about the fact that you’ve sacrificed optimized efficiency (today and tomorrow). The worst manifestations of these sacrifices must be adjusted for at the margin. And ditto if you’ve chosen to optimize for efficiency today! You have to be explicit about the fact that you’ve sacrificed optimizing for equity (today and tomorrow). The worst manifestations of these sacrifices must be adjusted for at the margin.

Two, no matter what your favored path is (and I envy you your conviction if you know that your path is The Best One For All, I really do), there will be errors along the way. That’s just life, there will be unexpected surprises along the way. Call it risk, or uncertainty, or whatever you like (and yes, I know, comparing the two is like comparing Knight and day) – but account for the fact that your battle plan will meet the enemy, and it will not survive.

You must adapt, and said adaptation will involve a series of continuing, even interminable decisions. - Those adaptations will land you somewhere in the middle of efficiency and equity. At which point, you can adapt your will to your circumstances and say you’ve found the truth, or you can continue with your decision-making. It is, after all, interminable.

- “Wait, so there’s no end to this?!”, I hear you ask in righteous indignation. “What is the eventual outcome? Or are we doomed to keep making these interminable decisions forever?”. Kids these days, I tell you. They’re just like kids in those days.

And that’s why I say what I did at the start of today’s post. The only change I’d make is the addition of one word:

The ability to exercise good judgment recursively is the binding constraint in development.