That is, of course, part of a very famous quote by Robert Solow:

You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics

http://www.standupeconomist.com/pdf/misc/solow-computer-productivity.pdf

And in a recent newsletter, Paul Krugman agrees:

…have the past few decades generally vindicated visionaries who asserted that information technology would change everything? Or have they vindicated techno-skeptics like the economist Robert Gordon, who argued in a 2016 book that the innovations of the late 20th and early 21st century were far less fundamental than those between 1870 and 1940?

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/04/opinion/internet-economy.html

Well, by the numbers, the skeptics have won the argument, hands down.

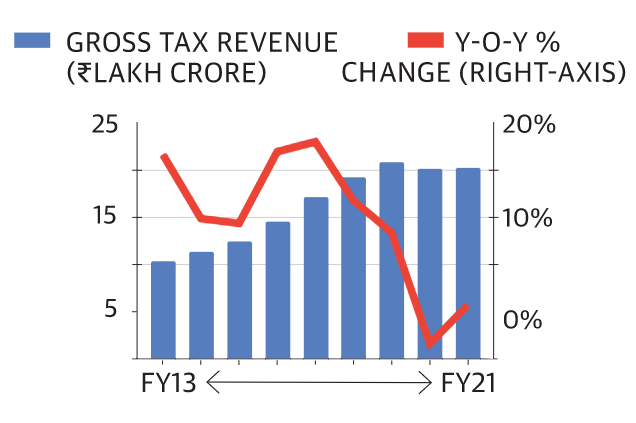

Paul Krugman goes on to show this chart:

I’ll tell you how to read this chart, but back up for a moment and learn about total factor productivity first:

Total Factor Productivity (TFP) is a measure of how much output an economy can produce using the same amount of inputs, like labor and capital.

chat.openai.com

In simpler terms, TFP is like a measure of how smartly an economy is using its resources to make things. It tells us how efficiently a country is using its workers, machines, and materials to create products and services.

TFP is important because it can help explain why some countries are richer than others. When a country can produce more with the same amount of inputs, it can grow faster and become richer over time.

Measuring TFP is tricky because it’s hard to tell how much of a country’s output is due to factors like capital and labor, and how much is due to other things like technology and innovation. To measure TFP, economists use complex models that take into account all the different factors that could be affecting a country’s productivity.

In the context of development economics and growth theory, TFP matters because it can help explain why some countries are able to grow faster and become richer than others. Countries that are able to improve their TFP can create more goods and services with the same amount of resources, which can lead to faster economic growth and higher living standards for their citizens.

To improve TFP, countries can invest in education and research, create better infrastructure, and implement policies that encourage innovation and entrepreneurship. By doing so, they can create a more productive and efficient economy that can grow and thrive over time.

So here’s the question to ask: did the advent of the internet allow us, as an economy, to get smarter at using our resources to make things? Paul Krugman’s chart answer this question by showing how TFP growth changed over the next twenty five years from each given date on the x-axis. So if in 1948, TFP growth was just below 2, what that means is that TFP growth over the period 1948-1973 was just below 2. So did TFP growth go up in a twenty-five year period following 1996? The chart clearly says no, it didn’t, and Paul Krugman says “Ha!“:

See the great productivity boom that followed the rise of the internet? Neither do I.

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/04/opinion/internet-economy.html

Here’s the paragraph that really stuck out for me, though, from Paul Krugman’s column:

For the fact is that while moving information around is important, we’re still living in a material world: Most of what we consume is physical stuff or in-person services, which haven’t been drastically affected by the internet.

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/04/opinion/internet-economy.html

Huh. Let’s try to think this through:

- Use your own example, as I am about to do below.

- Do you use online services, even when it comes to consuming physical stuff or in-person services? In my case, Amazon is where I buy most of my physical stuff from, or from Amazon’s competitors. But they all have an online presence, and that is my preferred mode of shopping.

- I much prefer to have my food delivered home via Zomato or its competitors. My consumption of music is via online streaming services, my consumption of video is via YouTube or via OTT, I don’t even have a cable connection at home. My consumption (and creation) of the written word is almost entirely online (blogs, Kindle, Twitter, newsletters in my inbox). A fair few chunk of my classes at various colleges are online every now and then.

- Calling a plumber home, or an electrician, is via Urban Company, or one of its competitors. Booking flight/train tickets, booking movie tickets, paying my daughter’s school fees, transacting with my bank – I can go on, but it’s mostly online.

- Software has eaten, I would say, most of my world.

- But I should ask if I am falling prey to confirmation bias. What is decidedly offline, for me, as a consumer?

- I should also be asking if I am truly representative of the average Punekar, let alone the average Maharashtrian, let alone the average Indian, and still lesser an average citizen of the world.

I would say this much: I’m fairly confident that the Internet has enabled more consumption of goods and services than was the case twenty-five years ago. As a sixteen year old in 1998, I can guarantee you that reading what Paul Krugman wrote a couple of days ago would have been a very hard thing to do! And I feel fairly safe in saying that at varying margins, this is true for a lot of people in Pune, in Maharashtra, in India, and indeed in the whole world. Those margins will likely be influenced by per capita income in each country, by whether you stay in a more (or less) urbanized part of the world, and by a whole host of other factors. But as a species, a lot of our consumption of even physical goods or in-person services has been impacted by the advent of the internet.

I’m very curious to hear from you, especially if you disagree. Please tell me what I’m missing out on!

But that makes Paul Krugman’s chart even more puzzling! I’m tempted to disagree with him based on what I’ve written above, but I’m not sure how to disagree with the chart.

What about you?

Measuring GDP is hard.

Paul Krugman’s post ends with a few cool references, and since it’s behind a paywall, I’m listing them over here:

First, a nice YouTube video on washing machines and the internet:

Second, a simple explainer on TFP.

Third, a lovely book by Robert Gordon which you absolutely must read.

Final point: how to get better at measuring GDP is (and will likely continue to be for a very long time) a fascinating problem, and I will definitely write more about it in future posts. But in the meantime, if you have any recommendations about what to read/listen/view, please do share!