First of all, congratulations to Philpp Strack!

And for those of you wondering about what the J.B. Clark medal is all about, here is the background:

The John Bates Clark Medal is awarded by the American Economic Association to “that American economist under the age of forty who is adjudged to have made a significant contribution to economic thought and knowledge.” The award is named after the American economist John Bates Clark (1847–1938).

According to The Chronicle of Higher Education, it “is widely regarded as one of the field’s most prestigious awards… second only to the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.” Many of the recipients went on to receive the Nobel Prizes in their later careers, including the inaugural recipient Paul Samuelson. The award was made biennially until 2007, but from 2009 is now awarded every year because of the growth of the field. Although the Clark medal is billed as a prize for American economists, it is sufficient that the candidates work in the US at the time of the award; US nationality is not necessary to be considered

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Bates_Clark_Medal

Now let’s say that you, as an enthusiastic student of economics, land up on the AEA page about the announcement. But less than halfway through the page, you begin to feel a familiar sensation. I pride myself on being able to express my thoughts reasonably well in English, but when you encounter a passage like this:

Strack’s rich extension of the canonical drift-diffusion model (with Fudenberg and Strzalecki, American Economic Review 2018) establishes a new benchmark in economics, psychology, and neuroscience for exploring the timing of choices. The extension incorporates uncertainty about payoffs and accounts for the selection of observed outcomes. This deeper exploration also gives rise to new statistical tests of the drift-diffusion model (with Fudenberg, Newey, and Strzalecki, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020). These, and his other contributions, have gone far in building bridges between theory and behavioral economics as well as between theory and empirical work.

https://www.aeaweb.org/about-aea/honors-awards/bates-clark/philipp-strack

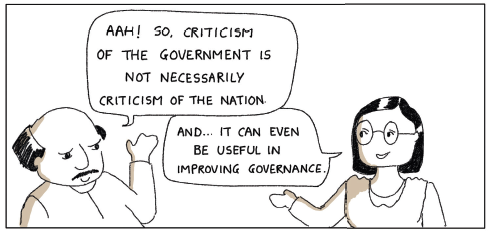

… there is only one appropriate response:

You could ask your prof in college to talk about it, you might ask your friends, you could ask your seniors. But if you are an undergraduate (or postgraduate, for that matter) student of economics – or even a person genuinely curious about economics in general – whatay time to be alive:

Hi. Philipp Strack has won the Clark medal in economics for 2024. I am going to share with you a PDF file of the announcement, which also contains some background of his more important work.

I am an undergraduate student of economics in India, and have some familiarity with microeconomic theory. I am familiar with Hal Varian’s “Intermediate Microeconomics”, but not all of the chapters – I’m familiar with the chapters concerning producer theory, consumer theory, exchange, information asymmetry, game theory and a little bit about risk and decision making. I have had an introductory lecture in behavioral economics, and know about the field, but not in a lot of detail.

I would like you to act as a person steeped in the history of microeconomics – how it has developed over time, and what important theoretical advancements have helped develop the field. I would also like you to act as a person who is well versed in simplifying advanced microeconomic concepts for beginners like me. You like using analogies, and you like explaining using relatable metaphors. As a person who is an expert in simplifying concepts so that students can understand them, you like taking a concept, simplifying it, and showing how it relates to (and adds to) what a student already knows. You like asking a couple of questions to make sure that your explanation has been understood, and you ask if it is ok for you to proceed to the next explanation. You always explain only one concept from the PDF at a time, and you begin with the one that is easiest to “get”, and progressively move towards concepts with a higher level of conceptual difficulty. Your style is conversational, somewhat informal, always upbeat, but without sacrificing technical accuracy and comprehensiveness. Please go over the PDF, and begin explaining the first concept that you deem appropriate. Engage me in a conversation about it, ascertain how much I know about the topic, and structure your explanation accordingly. Once you think I have understood a concept well enough, given your explanation and follow-on questions, ask if it is ok to proceed to explaining the next concept in the PDF. At the end of our conversation, I should have not just an appreciation of Philipp Strack’s work, but also an understanding of how his research has advanced the field of microeconomics. If you can recommend further reading for us to converse about, that will be great (papers, blogs, textbooks, essays, anything is fine). Please begin.

Try that prompt on for size in any AI of your choice (but please, pretty please, try and get access to one of the paid ones), and see where the conversation takes you.

Here is Claude with an explanation of the canonical drift-diffusion model, and how Strack’s contributions matter in this area of research:

Absolutely! Let’s break this down into more accessible terms.

Imagine you’re at an ice cream shop, trying to decide between two flavors: chocolate and vanilla. A basic economic model might assume that you’ll quickly choose the flavor that you prefer. But in reality, the decision process is often more complex.

The drift-diffusion model is a way of describing how people make decisions over time. Think of it like a mental tug-of-war. Each flavor has a certain appeal or “value” in your mind. As you consider your options, you accumulate evidence in favor of each choice, like weights on a balance scale. This process of gathering evidence is the “drift.”

However, this accumulation of evidence isn’t perfect. There’s some randomness or “diffusion” involved. Maybe you recall a fond childhood memory of vanilla ice cream, tilting the scale in that direction. Then you notice the rich aroma of the chocolate, pulling you back the other way.

Eventually, the evidence in favor of one option reaches a threshold, and you make your choice. The key point is that this decision isn’t instantaneous – it unfolds over time, and the timing of the choice can reveal important insights about your preferences and decision process.

What Strack and his colleagues did was extend this basic drift-diffusion model in some important ways. First, they incorporated uncertainty about payoffs. In our ice cream example, this could mean you’re not entirely sure how much you’ll enjoy each flavor. Maybe the chocolate looks appealing, but you’re worried it might be too rich.

They also accounted for the fact that we typically only observe the final choices people make, not the full process leading up to those choices. This is like seeing which ice cream you ultimately chose, but not knowing about your mental tug-of-war between chocolate and vanilla.

By building these realistic elements into the model, Strack and his team created a more powerful tool for understanding decision-making. They also developed new statistical tests that researchers can use to check whether real-world data fits the predictions of the drift-diffusion model.

The importance of this work is that it helps connect abstract economic theories to the nitty-gritty details of how humans actually think and choose. It’s a bridge between the idealized world of economic models and the messy reality of human psychology.

Does this help clarify what the passage is saying? Let me know if you have any other questions! And when you’re ready, we can dive into the next concept.

- AI isn’t a homework completion tool. I mean it is, but it’s like asking Marvin to open doors (high fives if you got that reference, and go read H2G2 if you didn’t).

- AI isn’t a teacher replacement tool (not yet, anyway), but it is already better than the teacher at personalizing explanations just for you, and in using examples that will resonate with you.

- “Explain this PDF to me” is a criminally short prompt. I’m not saying the prompt I designed is a perfect one, but make your prompts detailed. Give background about who you are, and what “role” you would like AI to play. Give context, outline your expectations, set the tone, share what levels of detail you are expecting, and continue to do so throughout your conversation.

- If you are a student with access to AI, there is no excuse for not learning well.

- If you are a student in a college or university right now, you have the opportunity to learn in ways that all of humanity up until this point never did, and it’s not friggin’ close.

- I cannot begin to tell you how much I envy you.