Yesterday’s post was about fiscal policy in China, and how difficult it is to get it just right.

Which is true enough, but Paul Krugman points out how even if China gets that bit right (and it is a big if!), it still will eventually come up against a much more intractable problem: demographics.

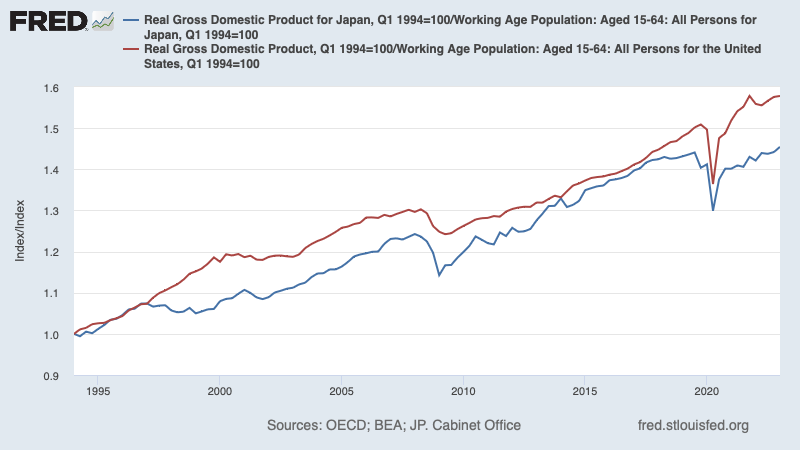

There’s some truth to aspects of this story, but it misses the most important factor in Japan’s relative decline: demography. Thanks to low fertility and unwillingness to accept immigrants, Japan’s working-age population has been declining quite rapidly since the mid-1990s. The only way Japan could have avoided a relative decline in the size of its economy would have been to achieve much faster growth in output per worker than other major economies, which it didn’t.

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/25/opinion/japan-china-economy.html

Krugman gos on to point out an underappreciated point. Relative to the troubles that Japan has gone through, it actually has not done all that badly. Far from it, in fact – it is doing rather well, relative to expectations:

By the way, if you’re unfamiliar with FRED St Louis, this would be a fun assignment to get you going. Try and recreate this chart by yourself.

So what worked with Japan? Paul Krugman hypothesizes that this may be due to Japanese society being dynamic and culturally creative. I haven’t been to Japan so far, but I cannot wait to go. Next year, fingers crossed.

But the obvious question, of course is whether China in the near future can manage what Japan did over the last thirty years. Paul Krugman thinks not:

Yet if China is headed for an economic slowdown, the interesting question is whether it can replicate Japan’s social cohesion — its ability to manage slower growth without mass suffering or social instability. I am very definitely not a China expert, but is there any indication that China, especially under an erratic authoritarian regime, is capable of pulling this off? Note that China already has much higher youth unemployment than Japan ever did. So, no, China isn’t likely to be the next Japan, economically speaking. It’s probably going to be worse.

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/25/opinion/japan-china-economy.html

Yesterday’s post was about problems in the near term for China. Today’s post is about long term problems in the case of Japan, and how they’ve dealt with it. Both perspectives are important, and if you are a student of economics, both really and truly matter:

I often begin introductory classes in macroeconomics by saying that there’s two reasons you might want to take your child to a doctor. I should know, I have a five year old daughter.

https://atomic-temporary-112243906.wpcomstaging.com/2018/10/09/links-for-9th-october-2018-aka-the-nobel-special/

The first reason is because the child has a cold say, or a fever. A temporary problem, that can hopefully be fixed in the “short run”. The other reason that you might want to take your child to a doctor is to figure out if your child is doing well on parameters such as height, weight etc. Any parent who has agonized over what percentile their child is on that accursed chart which shows “normal” height and weight knows what I’m talking about. These are “long run” parameters.

The economy is the same! We worry about short run problems, such as the deficit, or the annual budget, and well we should. But we should also be thinking long and hard about the long term growth prospects of ourchildreneconomy.

Note to readers: if you’re wondering why “democracy” in the title, ponder this phrase from Paul Krugman’s post: “especially under an erratic authoritarian regime”. Democracy may give you slow growth, but it is underrated, especially in today’s day and age.

Note to self: that five year old daughter will be ten years old next month! Where did time go?!