In last Wednesday’s post, I ended by saying this, in the context of recent scientific advancements:

But on a personal level, the past year has also taught me this, and I have Morgan Housel to thank for the central insight: the seeds of calm are planted by crazy.3

https://atomic-temporary-112243906.wpcomstaging.com/2021/03/24/whats-up-with-the-world-outside-of-covid-19/

So when things are really bad and grim (and again, this is not over yet), look to the bright side. And not just because it’s a good thing to do! But also because the bright side is likely to be brighter precisely because of everything else being so goddamn dark.

Tomorrow, I’ll attempt to answer a question I have, and I am sure you do as well: why?

I didn’t write the follow-up post, not because I forgot to, but because I couldn’t figure out how to think through what to write about. It turns out that I am still not sure! But in this post I’ll try and tell you why I’m not sure, what I’ve been thinking about, and what I’ve started reading to help me think through aspects of growth.

First, I think I’ve understood the central message of Tyler Cowen’s Stubborn Attachments, and agree with it: growth matters.((As I wrote towards the end of that post, the spread of learning is what I would want to maximize, but that learning contributes towards growth, and more growth leads to more learning, so we’re on the same page for the most part))

Which then begs the question: how should we promote more growth, and more learning?

More learning, for me, means dramatically changing (or perhaps entirely discarding) the way higher education is currently handled, and that’s something to think about for years to come.

More growth, for me, means trying to understand the nature of growth, why it occurs at all, how it occurs, and what factors contribute to and hamper growth. And this topic is, well, a rather large one. It is large in terms of building out an edifice around which I can attempt to learn more about the subject, let alone the actual learning itself.

Here is what I mean by that: when I think about growth, and find myself wanting to learn more about growth, I want to be systematic about the process. If I say I want to learn mathematics, for example, I’ll want to divide, in my head, different branches of the subject. Then learn about the topics, and the mathematicians associated with those topics, and drill down accordingly.

How to do that with growth?

Should we begin by analyzing all of human growth over all of its (available) history? Watch videos like this Ted Talk, go through courses such as this one, and read books such as this one? Or focus on one country/civilization and examine it’s growth over time? Say, the Indian civilization over time? Or modern India, since 1947? Or focus on a group of countries over a period of time, such as say Joe Studwell’s How Asia Works? Or all of the above?

The answer is, obviously, all of the above, but then in that case where to begin?

Hopefully you have been through the same process for different things/projects/concepts in your own life – that feeling of where to start, even?((I was tempted to use the excavator/Ever Given meme here. Please congratulate me for resisting the temptation.))

Here is how Robert Pirsig helped me understand the answer to that question:

A memory came back of his own dismissal from the University for having too much to say. For every fact there is an infinity of hypotheses. The more you look the more you see.

Pirsig, Robert M.. Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (p. 171). HarperCollins e-books. Kindle Edition.

She really wasn’t looking and yet somehow didn’t understand this.

He told her angrily, “Narrow it down to the front of one building on the main street of Bozeman. The Opera House. Start with the upper left-hand brick.”

Her eyes, behind the thick-lensed glasses, opened wide. She came in the next class with a puzzled look and handed him a five-thousand-word essay on the front of the Opera House on the main street of Bozeman, Montana. “I sat in the hamburger stand across the street,” she said, “and started writing about the first brick, and the second brick, and then by the third brick it all started to come and I couldn’t stop. They thought I was crazy, and they kept kidding me, but here it all is. I don’t understand it.”

The brick that I have chosen to begin with is Robert Gordon’s book, The Rise and Fall of American Growth. It is a rather large brick, at 784 pages, and I am only one chapter in, but it is already worthy of a blogpost.

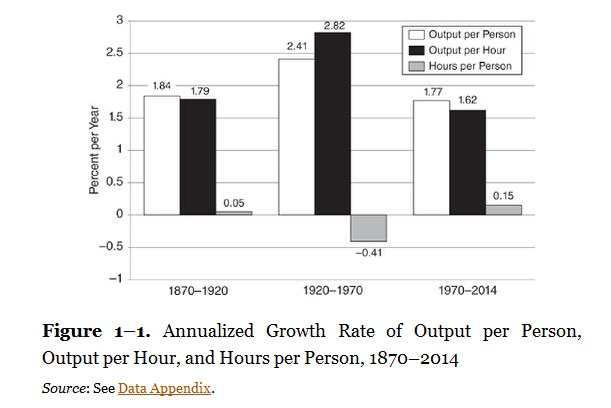

Consider this chart, for example:

The book focusses on the period 1870 through until 2014, and attempts to explain the cause, the nature and the effect of growth on the United States of America for that period. As I said, a rather large brick. And the chart above shows that most of the growth during this period occurs in fact between the period 1920-1970, when measured in terms of output per hour and output per person. Growth went up, in other words, the most in this period.

And what caused this growth?

It wasn’t education-augmented labor, or more machinery, but rather, Total Factor Productivity. Here’s a previous post about the Solow Model, if you want to learn more about TFP.

This, of course, begs the obvious question: why?

Why was growth so very impressive in that period? As a prospective answer, at least in that first chapter, Gordon supplies a hypothesis that we are familiar with here on EFE: Paul David’s essay about the dynamo and the computer.

So quite simply, it takes time for us as a society to accept, internalize and then optimize for a new technology. The invention of a new technology doesn’t necessarily imply its adoption. For example, and this is a true story, we still get invites for faculty meetings at my Institute by hand, not online calendar invites.

And so growth is clumpy for at least the following reasons:

- The discovery of a new technology doesn’t necessarily mean it’s immediate wholesale adoption

- This is partly because of inertia, resistance to change and the sunk cost fallacy

- And it is partly because we as a society simply take time to try and figure out how to make best use of the new technology.

This involves job losses, restructuring, adjustments – and not all of these processes are smooth or even remotely pleasant. The long run consequences of adopting new technology are beneficial, while the short run adjustments are anything but. Focusing on reducing short term pain might well induce more long term pain, but focusing on long term gain is an impractical solution for politicians and policy-makers on the ground, unless a crisis makes it imperative and (at least somewhat) acceptable.

Think driverless cars today (per the link above), or think 1991 economic reforms. Selling either of these things without the crisis of that particular time would have been harder than it already was. As Morgan Housel says, crazy plants the seed of calm.

Leading me to ask myself the question: is growth necessarily lumpy? Might we be worse off for attempting to change it’s lumpy nature? I don’t know the answer to these questions, but they are questions worth keeping in mind as I proceed with Gordon’s book.