The 'Institutional Yes' at Amazon. Bosses are supposed to say Yes to new ideas. If they reject, they have to write a two-page thesis explaining why it is a bad idea. AWS was born out of the Institutional Yes. Harvard Business Review (2007) article on this: https://t.co/V3SCinItTm pic.twitter.com/XNwwr0Zunc

— Sachin Kalbag (@SachinKalbag) July 22, 2023

Tag: amazon

Jeff Bezos, ex-CEO, Amazon

I thoroughly enjoyed going through these pictures, and you probably will too.

Here are three things I’d recommend you read about Amazon, to get a better sense of the company and what it has been up to:

- The Everything Store, by Biz Stone

- The Amazon Tax, by Ben Thompson

- A fascinating story about how Amazon developed it’s batteries.

Airtel, Amazon, and Untangling Some Thoughts

Capital Mind, one of my favorite blogs to read, recently posted an excellent write-up on how Bharti Airtel is faring over the last three to four years. You might have to sign up in order to read it, but happily, Capital Mind allows you a free trial, so you should still be able to access it.

Why do I think you should read it, and why am I talking about this today? Because we need to think about telecommunications, technology, monopolies, scale, regulations, FDI in order to understand why Amazon may well be interested in buying Airtel, or at least in owning a stake.

Airtel has issued a boilerplate disclaimer since, but, well. Come on.

But hang on a second. We first need to get a basic framework in place, before we start thinking about everything else.

Our framework will consist of three things (or actions) that we tend to do on the internet, three international behemoths that are very, very interested in India, and three telecommunications firms that are very heavily invested in India.

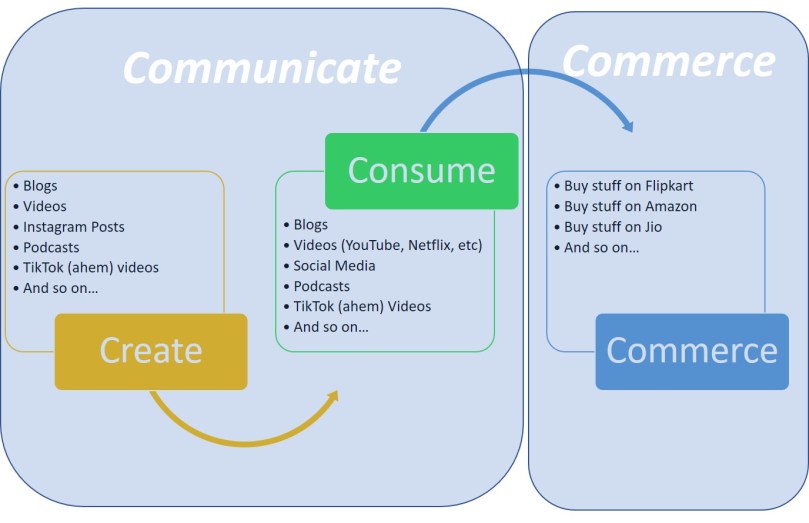

First, the three things that all of us tend to do on the Internet. We create content, we consume content and we engage in commerce.

Let’s begin with the one in the middle. When you’re lying on your sofa at three in the morning, flicking through Netflix’s endless library of content, you are very much a consumer. When you roll your eyes at the latest dripping-with-insanity forward you receive on your family Whatsapp group, you are a consumer of content online. When you run a search for a PDF that will help you finish an assignment in college: consumer. For most of us, the internet enables us to consume stuff at levels that have never before been possible. Music, videos, podcasts, the written word: all consumption.

Now let’s move on to the one on the left: creation. You weren’t around when I wrote these words that you are reading, but I was creating stuff. Your latest Instagram story? Creation of content. The latest GIF that you created before sharing it? Creation of content. Do you upload videos on Insta/YouTube/Vimeo? Do you blog? Do you create podcasts? All content creation.

And finally, the reason Jeff and Mukesh are as rich as they are: commerce. Online shopping is literally blowing up in front of our eyes in terms of value. Amazon, Flipkart, Nykaa, all of Jio’s online shopping, MakeMyTrip, Oyo, Airbnb, Uber, Zomato… the list is endless, and exhausting. That’s the third thing you do online. Commerce.

Ah, you might say. What about a Whatsapp call with friends, or a Skype call with family, or a Zoom online seminar (god help us all)? That’s arguably consumption and creation at the same time, no?

Well yes. Or call it communication.

Creation and consumption of content are really two sides of the same coin, and when they happen simultaneously, they are all of what we spoke about in the last paragraph.

There is a world of thinking to be done about the blue rectangle on the left. About how Google cornered the consumption of stuff online using Gmail, Google Maps etc, by piggybacking on it’s search monopoly, and about how Facebook took away the search monopoly by creating its own walled garden and making Google search irrelevant within it, and how Google tried to respond with Google Buzz-no-Wave-no-Plus-no-WhateverNext and failed… and this can go on. But here’s the quick takeaway:

When it comes to content creation, or content consumption, or communication, Google and Facebook have the market pretty much tied up between them. The battle for who wins between them will continue for a while, and it will be a fascinating story, but for our purposes, it is enough to realize for today that Google and Facebook are mostly on the left. That’s not entirely true (Google Play Store, Froogle, Facebook Marketplace being just some examples), but it’s good enough for now.

Google and Facebook are mostly communication based firms who dabble in commerce.

And Amazon, of course, is the easiest example to think of when it comes to online commerce. The Amazon app, sure, but also its delivery and logistics arm, and, of course, AWS. If I want to buy stuff online, Amazon is literally the first – and more often than not, the only – thing that comes to mind. Zomato and Swiggy for food, Uber and Ola for travel, OYO and Airbnb for hotels/lodging, MakeMyTrip/Cleartrip/Yatra for travel are also very valid examples. But we’re, as consumers, not passively consuming content over here in this space: it is a very specific transactional approach.

But then things began to get complicated.

Consider Amazon. Commerce company, very much so. But what about Amazon Prime Video? What about Amazon Prime Music? What about Amazon Photos? What about Alexa and the Echo family?

Or consider Google. What about, as we have already mentioned, the Google Play Store? What about Froogle? What about Play Movies, Play Books?

Our neat little framework now has overlaps, and there are insurgencies along this virtual boundary. But we can add to our framework to help us keep it relatively simple:

Google, which is a firm that started life as a software firm, then started to make hardware as well (Nexus, Pixel, Chromebooks, Pixel tablets, Google Glass etc). Of course people could create and consume content on these devices. Of course these devices would help Google learn more about the people who owned these devices. But wouldn’t it be great (Google thought) if we could make moaarrrrr money by using this gleaned information ourselves? Hey, let’s get into commerce.

Facebook tried to say the same thing, but with rather more limited success.

And Amazon, a firm that started life as an online seller, started to make hardware as well, precisely so as to learn more about people’s consumption habits online and offline. That’s the Echo devices, the Kindle, the Firestick and so on.

And don’t forget Apple! They no longer can rely on selling hardware alone for growth, mostly because they have already sold all the devices they possibly can to as many people as they possibly can (at least in the USA, but they’re coming for you too). And so, services! Apple Music, Apple TV, iCloud – all of these are not hardware related, they’re all about consumption of content.

So even our latest attempt at simplifying the framework fails, because none of these blue rectangles are neat and delineated: firms from every blue rectangle want to be present in the creation, consumption and commerce space.

They want to do this for a variety of reasons, but the most important reason is simply the following: they’d much rather get a “360 degree” view of their consumer, without having to rely on some other firm to share information.

If, for example, Jio manufactures the device I use to go online (JioPhone), and I log on to that device to watch JioTV, and visit Ajio to buy clothes using that device, and post about the sneakers I just bought on a social media platform owned by Jio (or well, something like that), then I’ve obviated the need for Google! Neither the device, nor the steaming platform, nor the shopping platform, nor the social media has anything to do with Google. How then, does Google know me enough to advertise effectively to me?

But, if I use a Pixel phone to stream content on my Chromecast device, and buy a pair of sneakers on Flipkart (well, in a parallel universe…) and post about it on whatever is Google’s next attempt to build a social media platform, I’m living entirely in the Google Universe.

It’s no longer about companies living in one blue rectangle, you see. It is about one company dominating all blue rectangles, and so knowing everything there is to know about the consumer. That’s the end game here.

And speaking of all blue rectangles…

And that, my friends, is why Amazon wants to be friends with Airtel, Google wants to be friends with Vodafone.

Because Mukesh has his finger in each of these pies, and Mark has acknowledged as much.

Homework: as a consumer, and as an investor, which of the three are you betting on? Amazon, Google or Jio? Why?

How do you interact with your computer?

“Alexa, play Hush, by Deep Purple.”

That’s my daughter, all of six years old. Leave aside for the moment the pride that I feel as a father and a fan of classic rock.

My daughter is coding.

My dad was in Telco for many years, which was what Tata Motors used to call itself back in the day. I do not remember the exact year, but he often regales us with stories about how Tata Motors procured its first computer. Programming it was not child’s play – in fact, interacting with it required the use of punch cards.

I do not know if it was the same type of computer, but watching this video gives us a clue about how computers of this sort worked.

The guy in the video, the computer programmer in Telco and my daughter are all doing the same thing: programming.

What is programming?

Here’s Wikiversity:

Programming is the art and science of translating a set of ideas into a program – a list of instructions a computer can follow. The person writing a program is known as a programmer (also a coder).

Go back to the very first sentence in this essay, and think about what it means. My daughter is instructing a computer called Alexa to play a specific song, by a specific artist. To me, that is a list of instructions a computer can follow.

From using punch cards to using our voice and not even realizing that we’re programming: we’ve come a long, long way.

It’s one thing to be awed at how far we’ve come, it is quite another to think about the path we’ve taken to get there. When we learnt about mainframes, about Apple, about Microsoft and about laptops, we learnt about the evolution of computers, and some of the firms that helped us get there. I have not yet written about Google (we’ll get to it), but there’s another way to think about the evolution of computers: we think about how we interact with them.

Here’s an extensive excerpt from Wikipedia:

In the 1960s, Douglas Engelbart’s Augmentation of Human Intellect project at the Augmentation Research Center at SRI International in Menlo Park, California developed the oN-Line System (NLS). This computer incorporated a mouse-driven cursor and multiple windows used to work on hypertext. Engelbart had been inspired, in part, by the memex desk-based information machine suggested by Vannevar Bush in 1945.

Much of the early research was based on how young children learn. So, the design was based on the childlike primitives of eye-hand coordination, rather than use of command languages, user-defined macro procedures, or automated transformations of data as later used by adult professionals.

Engelbart’s work directly led to the advances at Xerox PARC. Several people went from SRI to Xerox PARC in the early 1970s. In 1973, Xerox PARC developed the Alto personal computer. It had a bitmapped screen, and was the first computer to demonstrate the desktop metaphor and graphical user interface (GUI). It was not a commercial product, but several thousand units were built and were heavily used at PARC, as well as other XEROX offices, and at several universities for many years. The Alto greatly influenced the design of personal computers during the late 1970s and early 1980s, notably the Three Rivers PERQ, the Apple Lisa and Macintosh, and the first Sun workstations.

The GUI was first developed at Xerox PARC by Alan Kay, Larry Tesler, Dan Ingalls, David Smith, Clarence Ellis and a number of other researchers. It used windows, icons, and menus (including the first fixed drop-down menu) to support commands such as opening files, deleting files, moving files, etc. In 1974, work began at PARC on Gypsy, the first bitmap What-You-See-Is-What-You-Get (WYSIWYG) cut & paste editor. In 1975, Xerox engineers demonstrated a Graphical User Interface “including icons and the first use of pop-up menus”.[3]

In 1981 Xerox introduced a pioneering product, Star, a workstation incorporating many of PARC’s innovations. Although not commercially successful, Star greatly influenced future developments, for example at Apple, Microsoft and Sun Microsystems.

If you feel like diving down this topic and learning more about it, Daring Fireball has a lot of material about Alan Kay, briefly mentioned above.

So, as the Wikipedia article mentions, we moved away from punch cards, to using hand-eye coordination to enter the WIMP era.

It took a genius to move humanity into the next phase of machine-human interaction.

https://twitter.com/stevesi/status/1221853762534264832

The main tweet shown above is Steven Sinofsky rhapsodizing about how Steve Jobs and his firm was able to move away from the WIMP mode of thinking to using our fingers.

And from there, it didn’t take long to moving to using just our voice as a means of interacting with the computers we now have all around us.

Voice operated computing systems:

That leaves the business model, and this is perhaps Amazon’s biggest advantage of all: Google doesn’t really have one for voice, and Apple is for now paying an iPhone and Apple Watch strategy tax; should it build a Siri-device in the future it will likely include a healthy significant profit margin.

Amazon, meanwhile, doesn’t need to make a dime on Alexa, at least not directly: the vast majority of purchases are initiated at home; today that may mean creating a shopping list, but in the future it will mean ordering things for delivery, and for Prime customers the future is already here. Alexa just makes it that much easier, furthering Amazon’s goal of being the logistics provider — and tax collector — for basically everyone and everything.

Punch cards to WIMP, WIMP to fingers, and fingers to voice. As that last article makes clear, one needs to think not just of the evolution, but also about how business models have changed over time, and have caused input methods to change – but also how input methods have changed, and caused business models to change.

In other words, understanding technology is as much about understanding economics, and strategy, as it is about understanding technology itself.

In the next Tuesday essay, we’ll take a look Google in greater detail, and then about emergent business models in the tech space.

Kindle, Vancouver, Onions, Government Size and Quizzing

Five articles that I enjoyed reading this week, with a couple of sentences on why I think you might benefit from reading them.

The extent to which Amazon, via the Kindle, tracks your reading habits. Most of this article did not come as a surprise to me, and of course the Kindle and the books on it are as cheap as they are precisely because Amazon makes money by tracking precisely what this article says they do. Personally, I am OK with that – but you might want to read this before you make your own decision.

Could Amazon’s monopoly over the publishing industry change the nature of books themselves? As a result of the economic pressures of the streaming industry, the length of the average song on the Billboard Hot 100 fell from 3 minutes and 50 seconds to 3 minutes and 30 seconds between 2013 and 2018. Will books be the next art form to be altered? Greer said it is possible.

“Never underestimate the power, or willingness, of tech companies to do almost anything to make a little extra money – including shifting the entire way we make music or read and write books,” she said. “They are perfectly willing for art to be collateral damage in their pursuit of profit.”

The equilibrium is being solved for in Vancouver, by observing the lack of an equilibrium in other cities. On Uber, Lyft, British Columbia, and the last mover advantage:

“A decade after Uber got its start, and eight years after Lyft changed the ride-hail model by allowing anyone to use their everyday car to pick up passengers, British Columbia thinks it has nailed how to regulate these companies, which have often slipped into the gray areas between transportation and labor laws. Call it the last mover advantage. Government officials in the province have spent years studying how other places dealt with an influx of ride-hail vehicles—and the sometimes unfortunate effects they had on local transportation systems.”

Vivek Kaul explains one application of the law of unintended consequences in this article in the Livemint, about onions.

When prices of an essential commodity, like onions, go up, state governments can impose stockholding limits. This leads to a situation where wholesalers, distributors and retailers dealing in the essential commodity need to reduce the inventory that they hold in order to meet the requirements of a reduced stock limit. The idea is to curb hoarding, maintain an adequate supply of the essential commodity and, thus, maintain affordable prices. This is where the law of unintended consequences strikes. Instead of ensuring prices of the essential commodity remain affordable, ECA makes it expensive.

Small governments aren’t necessarily great governments, but large governments don’t always do well either. But if you must choose when it comes to government, size does too matter! Via Marginal Revolution.

The plots do not support the hypothesis that small government produces either greater prosperity or greater freedom. (In reading the charts, remember that the SGOV index is constructed so that 0 indicates the largest government and 10 the smallest government.) Instead, smaller government tends to be associated with less prosperity and less freedom. Both relationships are statistically significant, with correlations of 0.43 for prosperity and 0.35 for freedom.

Samanth Subramanian on the joy of quizzing.

To attend these contests, quizzers rearrange the furniture of their lives, budgeting their time away from their families, or ensuring that they don’t travel overseas for work during a quiz weekend. I know one quizzer who switched jobs because his city’s quiz scene wasn’t active enough; I know another who scheduled his wedding to avoid a clash with a quiz. Once, while we were waiting around for a popular annual quiz to begin, a friend remarked that his wife was heavily pregnant; he hoped she wouldn’t go into labour over the next few hours. That would be unfortunate, we agreed.

“No, you don’t understand,” he said. “If my daughter’s born today, that means she’ll have a birthday party on this date every year. Which means I can never come to this quiz again.”

Tech: Understanding Mainframes Better

My daughter, all of six years old, doesn’t really know what a computer is.

Here’s what I mean by that: a friend of hers has a desktop in her bedroom, and to my daughter, that is a computer. My laptop is, well, a laptop – to her, not a computer. And she honestly thinks that the little black disk that sits on a coffee table in our living room is a person/thing called Alexa.

How to reconcile – both for her and for ourselves – the idea of what a computer is? The etymology of the word is very interesting – it actually referred to a person! While it is tempting to write a short essay on how Alexa has made it possible to complete the loop in this case, today’s links are actually about understanding mainframes better.

Over the next four or five weeks, we’ll trace out the evolution of computers from mainframes down to, well, Alexa!

- “Several manufacturers and their successors produced mainframe computers from the late 1950s until the early 21st Century, with gradually decreasing numbers and a gradual transition to simulation on Intel chips rather than proprietary hardware. The US group of manufacturers was first known as “IBM and the Seven Dwarfs”: usually Burroughs, UNIVAC, NCR, Control Data, Honeywell, General Electric and RCA, although some lists varied. Later, with the departure of General Electric and RCA, it was referred to as IBM and the BUNCH. IBM’s dominance grew out of their 700/7000 series and, later, the development of the 360 series mainframes.”

..

..

Wikipedia’s article on mainframes contains a short history of the machines.

..

.. - “Mainframe is an industry term for a large computer. The name comes from the way the machine is build up: all units (processing, communication etc.) were hung into a frame. Thus the maincomputer is build into a frame, therefore: MainframeAnd because of the sheer development costs, mainframes are typically manufactured by large companies such as IBM, Amdahl, Hitachi.”

..

..

This article was written a very long time ago, but is worth looking at for a simple explanation of what mainframes are. Their chronology is also well laid out – and the photographs alone are worth it!

..

.. - “Although only recognized as such many years later, the ABC (Atanasoff-Berry Computer) was really the first electronic computer. You might think “electronic computer” is redundant, but as we just saw with the Harvard Mark I, there really were computers that had no electronic components, and instead used mechanical switches, variable toothed gears, relays, and hand cranks. The ABC, by contrast, did all of its computing using electronics, and thus represents a very important milestone for computing.”

..

..

This is your periodic reminder to please read Cixin Liu. But also, this article goes more into the details of what mainframe computers were than the preceding one. Please be sure to read through all three pages – and again, the photographs alone are worth the price of admission.

..

.. - A short, Philadelphia focussed article that is only somewhat related to mainframes, but still – in my opinion – worth reading, because it gives you a what-if idea of the evolution of the business. Is that really how the name came about?! (see the quote about bugs below)

..

..

“So Philly should really be known as “Vacuum Tube Valley,” Scherrer adds: “We want to trademark that.” He acknowledged the tubes were prone to moths — “the original computer bugs.”

..

.. - I’m a sucker for pictures of old technology (see especially the “Death to the Mainframe” picture)

Tech: Links for 17th December, 2019

Five articles from The Ken today.

This is not, by any means, either an endorsement or a recommendation to subscribe to The Ken, neither do I have any contacts at this website. I have been a subscriber for a while now (though not yet a paying one), and I wanted to share a selection of their free articles to acquaint you with their write-ups, their business, and to familiarize you some alternative business models in the world of media.

- On the food delivery plastic problem (menace?) in India.

..

..

“Aggregators are stuck in an awkward spot between arbitrary regulations on plastic containers, and a partner network that, at best, is extremely heterogeneous in its attitude towards reducing plastic waste at source. The lack of suitable alternatives makes the job even harder. By Zomato’s own account, plastic waste from online food delivery adds almost 22,000 metric tonnes to India’s garbage pile every month, most of which, they admit, is dumped sans recycling.”

..

.. - “The Indian grocery market is currently a $400-$500 billion market, according to Ankur Pahwa, head of e-commerce and consumer internet at advisory services firm EY. However, says Pahwa, the penetration of e-commerce in this space is just 0.5% at the moment because of the supply chain challenges involved. Despite this, Pahwa predicts the share of online groceries will double by 2021.”

..

..

Cracking the un-crackable: dealing with groceries and hyperlocal deliveries in India.

..

.. - What’s bugging TrueCaller? No excerpts: read the whole thing! Also, yes, I have uninstalled the app after reading this.

..

.. - “Tesla’s hardly the only one powering the shift to lithium. Battery-makers like Korea’s LG Chem, China’s BYD and CATL, as well as Japan’s Panasonic are doubling down on lithium-ion battery production to capture the world’s largest electric vehicle (EV) market in China.

With a mission to electrify 30% of its vehicles by 2025, what share does India have of this global, lucrative and largely Asian manufacturing pie?

Currently, zero.”

..

..

On trying to understand why India doesn’t have a gigafactory yet – and might not in the near future, with a short concluding section on how to make the best of what is a bad situation.

..

..

5. “Hotstar’s watershed moment came in May 2019, when it broke its own global record of 10.3 million concurrent viewers. 18.6 million watched the final game of the Indian Premier League (IPL) cricket tournament during the weekend of 11-12 May. It shattered the record again in July when 25.3 million tuned in to watch India take on New Zealand in the Cricket World Cup semi-final.

But its appeal isn’t just sports. Hotstar has given viewers major titles like Game of Thrones—which it said was its most popular show in 2019—and blockbuster films like Marvel’s Avengers: End Game.”

..

..

On understanding Hotstar better.

Tech: Links for 26th November, 2019

- “Basecamp says Basecamp Personal is designed “specifically for freelancers, students, families, and personal projects,” and with it, you can make spaces for up to three projects, work on these projects with up to 20 users, and store up to one gigabyte of data in those projects. The new tier seems to put Basecamp in direct competition with free tiers from other project management tools like Asana and Trello, as well as workplace chat software like Slack and Microsoft Teams.”

..

..

Basecamp launches a new, free tier of its project management software – and it is certainly worth signing up.

..

.. - “The bus ticket theory is similar to Carlyle’s famous definition of genius as an infinite capacity for taking pains. But there are two differences. The bus ticket theory makes it clear that the source of this infinite capacity for taking pains is not infinite diligence, as Carlyle seems to have meant, but the sort of infinite interest that collectors have. It also adds an important qualification: an infinite capacity for taking pains about something that matters.”

..

..

Lots to unpack in this latest essay by Paul Graham.

..

.. - “As Kristal’s business grew, she needed help with all this unboxing and re-boxing, so she started looking for a prep center. There were about 15 at the time, she says, mostly in New Hampshire, Oregon, and Delaware, which have no sales tax. That way, sellers can enter the address of their prep center when they buy from Target’s website and pad their margins by a couple percent. Montana has no sales tax either, Kristal mused, and there wasn’t a single center in the online directory. Sensing an opportunity, she decided to give prepping a try. She chose a name — Selltec — and put it up on the directory, too.”

..

..

Who ever gets bored learning more about Amazon? Heard of a town called Roundup?

..

.. - “These newfangled warehouses have come up in Bhiwandi — known for its century-old power looms industry which still exists in the interiors of the city — only in the last five years or so. Here, online retail companies such as Amazon, Flipkart, Nykaa, Pepperfry, Grofers and Bigbasket, among others, store their goods in what the industry calls fulfilment centres or FCs. When a customer places an order on one of these online platforms, the item ordered is packed in these FCs, sorted according to the delivery location and dispatched in a delivery vehicle for its final destination. Third-party logistics companies (called 3PLs) such as DHL, Blue Dart, DTDC, Safexpress — the entities that deliver these goods to the customers’ doorsteps — also have their own FCs here. Like a local train on a busy Mumbai station, a delivery truck enters and exits these centres every 30 seconds.”

..

..

Meanwhile, in Bhiwandi…

..

.. - “But Musk says he knows what went wrong, and explained things on Twitter. Right before the metal ball test, von Holzhausen smacked the door with a sledgehammer on stage to prove its durability (and unlike the glass, it was fine), and Musk says this impact “cracked base of glass,” which is why the windows subsequently smashed when hit by the ball.”

..

..

Ah ok then.

Etc: Links for 15th November, 2019

- Bibek Debroy about Abhijit Banerjee’s father. This was fascinating!

..

..

“There were people who didn’t have an exceptional publication record. They were simply superb teachers.Dipak Banerjee was one of them. Except for a paper on utility he wrote while he was at LSE (London School of Economics), he rarely published. He was an exceptional teacher who produced exceptional students. Bhaskar Dutta, Subhashis Gangopadhyay, Dilip Mukherjee and Debraj Ray should be familiar names. They (all Dipak Banerjee’s students) edited a collection of essays in his honour in 1990. Mihir Rakshit primarily taught us macroeconomics and Dipak Banerjee primarily taught us microeconomics. Mihir babu’s teaching was precise. He never deviated from the topic. Dipak babu’s teaching was also precise, but he deviated from the topic and told us “stories”, especially at tutorials. In the course of these stories, we learnt he had two sons. He wasn’t worried about his younger son, who was “street smart”. But he worried about his elder son, who wasn’t that street smart. We learnt this elder son was called Jhima and that he had a middle name of Vinayak because he was born in Mumbai and because his mother (Nirmala Banerjee) was a Maharashtrian.”

..

.. - A short article about the “perils” of Amazon Prime

..

..

“”Because of multiple Prime orders, Amazon has had to think more about packaging. Recognizing some customers’ “wrap rage,” they are using more bubble envelopes. Aware that the excessive space occupied by smaller inexpensive items increases transport costs, they’ve been developing algorithms that match box size to contents to avoid “over-boxing.” And they want manufacturers to know that online packaging needs to be compact rather than attractive.”

..

.. - “We therefore predicted that reactivating previously unsolved problems could help people solve them. In the evening, we presented 57 participants with puzzles, each arbitrarily associated with a different sound. While participants slept overnight, half of the sounds associated with the puzzles they had not solved were surreptitiously presented. The next morning, participants solved 31.7% of cued puzzles, compared with 20.5% of uncued puzzles (a 55% improvement).”

..

..

Fascinating is an understatement – Alex Tabarrok on being productive while sleeping.

..

.. - “For me, sleep is the #1 important factor for my cognitive productivity. I typically get between 6½–7¼ hours per night. Much less, and I feel my brain turning to goo when I try to do anything cognitively demanding. I track my sleep with a fitness tracker so I can anticipate when I should expect a “bad day” and plan accordingly.”

..

..

On the importance of sleep, and holidays. Please look up Jensen’s inequality as well.

..

.. - “…music streaming subscriptions are typically far cheaper in emerging markets than they are in the US and Europe, but hardware built to play that music – often from the very same companies running the music services – is significantly more expensive.”

..

..

I pay 179 INR per month for Spotify – for six family members. INR 189 per month for YouTube Premium – for six family members.

EC101: Links for 24th October, 2019

Five articles about spends during the festive season in India this year:

- “Whether government stimulus packages announced so far will have an impact on festive consumption is a big question. An even bigger question is whether consumers, who are coping with flat-lining incomes and a poor job market, will respond to the incentives offered by companies. If this Diwali fails to sparkle in terms of consumption demand growth, outlook for the next few quarters will get much gloomier.”

..

..

The ET explains the importance of the Diwali season sales for India’s economy. A useful set of charts.

..

.. - “Sawai Makwana, 41, who runs a hair salon and a cafe in Jaipur, is a worried man. This will be my worst Diwali in nearly 30 years, he says. A third-generation hair stylist, Makwana says his business took its first hit in 2016, as a result of demonetisation. Matters have grown progressively worse since he has been forced to close down a section of his salon and sack 14 of his 16 employees. Male customers, who would spend an average of Rs 2,500, have either stopped coming or now just ask for a basic haircut that costs Rs 300, he laments.”

..

..

Always (always!) be wary of biased sampling and poorly researched articles – but here’s an article from India Today about the same topic.

..

.. - TechCrunch on how Amazon and Flipkart are dealing with the crisis.

..

.. - On the growth in Tier 2, 3 and 4 towns and how they impact these sales.

..

.. - And circling back to the ET, early reports seem to indicate that things weren’t quite as bad as was being feared.