You might want to read my previous posts about online education and learning before reading this. See this essay about the state of higher education in India, this about signaling and bundling in higher education, this about unbundling college and this about measuring efficiency in education.

In addition, Aadisht had a great comment about optionality and higher education, which really deserves a post in its own right – but you can click on the link in this paragraph and scroll to the bottom to read it for now.

All that being said, today’s post ties together the thoughts and deeds of three people whose thinking I try to follow very carefully when it comes to online education.

The role of community in education

Let’s begin with this tweet from one of them, David Perell.

Both the thread of which 4. is a part, and the Twitter thread referenced in 4. are worth reading.

But today, I wanted to focus on the community bit.

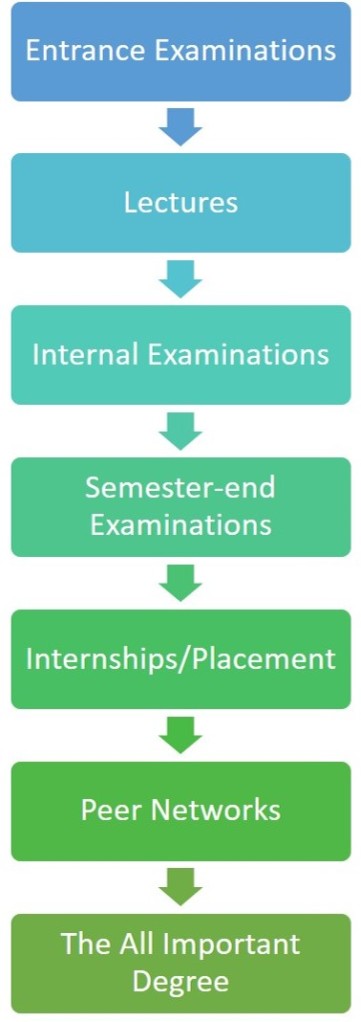

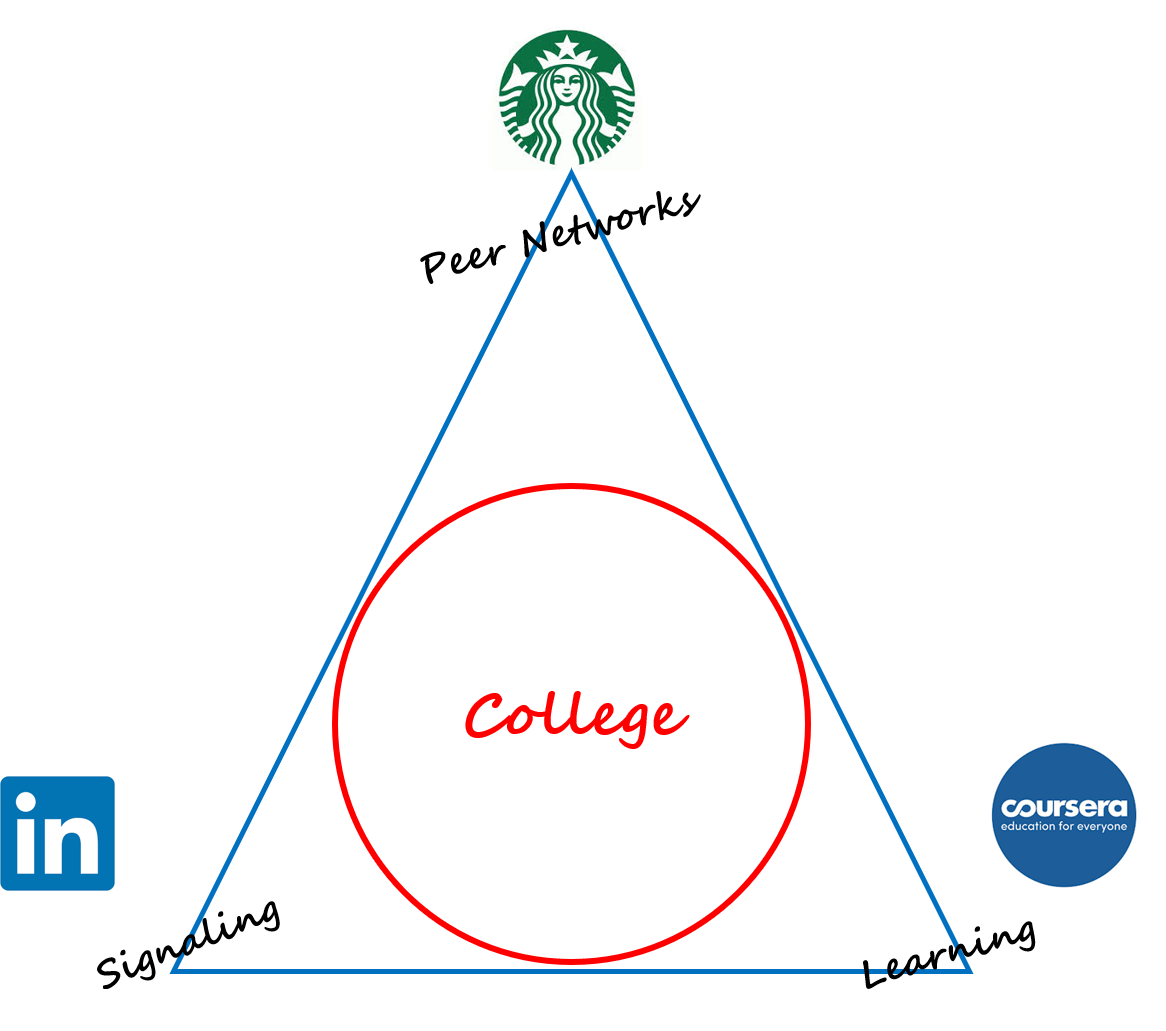

A quick reminder: my thesis is that college sells you three things. The education itself, the access to peer networks and the credentialing. If there is to be an online model that will work for colleges, it must successfully provide all three (and more) at the same price (or less) as college does today.

When it comes to peer networks, can they ever be as successful online as they have been offline?

That begs the question: have they been successful offline? And that is really two separate questions.

About Peer Groups

- Are peer groups worth the effort in the first place?

- Is there something special about peer groups you form in college?

With regard to the first, I’m going to take a pass on answering it in depth for at least two reasons. First, I know nowhere near enough sociology to be able to speak about this sensibly for any length of time. And second, isn’t the answer obvious?

About the second question, you might want to read this essay – a part of which is excerpted below:

As external conditions change, it becomes tougher to meet the three conditions that sociologists since the 1950s have considered crucial to making close friends: proximity; repeated, unplanned interactions; and a setting that encourages people to let their guard down and confide in each other, said Rebecca G. Adams, a professor of sociology and gerontology at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. This is why so many people meet their lifelong friends in college, she added.

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/15/fashion/the-challenge-of-making-friends-as-an-adult.html

The entire essay is worth your time, but the crux of it is those three points above: proximity; repeated, unplanned interactions; and college life.

Anecdote Time

Two of the best years of my life were spent while studying for my Masters degree at the Gokhale Institute in Pune. There was a fair bit of reading/learning involved, but most of those two years were spent in just hanging out with a group of people I am still close friends with.

And of the three things that Gokhale Institute gave me when I purchased a Masters degree from it, it is this group of friends that I value the most. Then comes the degree, and the least important – as it turns out – was the learning itself.

Don’t misunderstand me – learning was and is important! It’s just that for me, sitting in a class and listening to professors talk wasn’t the best way to learn. I have learnt much more by speaking one-on-one with some professors, arguing heatedly and passionately about random topics with friends, and by reading/listening/viewing to stuff on my own time.

But therein lies a dilemma.

How to reconcile online education with forming your college gang?

Random bike rides, conversations at three in the morning sitting on a ledge on the hostel terrace, giggling at a joke while sitting towards the back of a classroom is not just an important part of college. In my personal experience, this pretty much was college.

And not just during the pandemic, but even beyond, the key challenge is to figure out ways and means to achieve something approaching the same experience in this brave new online world of ours.

What might be an answer to this conundrum? That brings me to the second person whose thoughts about online education matter to me, Tyler Cowen

Small Group Theory, via Tyler Cowen

If you are seeking to foment change, take care to bring together people who have a relatively good chance of forming a small group together. Perhaps small groups of this kind are the fundamental units of social change, noting that often the small groups will be found within larger organizations. The returns to “person A meeting person B” arguably are underrated, and perhaps more philanthropy should be aimed toward this end.

Small groups (potentially) have the speed and power to learn from members and to iterate quickly and improve their ideas and base all of those processes upon trust. These groups also have low overhead and low communications overhead. Small groups also insulate their members sufficiently from a possibly stifling mainstream consensus, while the multiplicity of group members simultaneously boosts the chances of drawing in potential ideas and corrections from the broader social milieu.

https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2018/06/best-analyses-small-innovative-productive-groups.html

If you are going to run an online course, or are going to be a student enrolled in an online course, the most important thing you can do is think long and hard about forming groups.

If you are the person running the course, you need to make the process of forming a group as friction-less as you possibly can. Without these groups, not only are drop-outs more likely, but the groups themselves are perhaps the bigger point!

Here’s Tyler Cowen again, in a separate post:

Remember Lancastrian methods of education from 19th century England? Part of the idea was to keep small group size, and economize on labor, by having the students teach each other, typically with the older students instructing the younger.

https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2020/05/my-weird-lancastrian-method-for-reopening-higher-education.html

The post I quoted from is about how college might reinvent itself in the era of the pandemic, but the larger point he is making – or at any rate, the point I choose to take away – is about how learning in small groups is better than classrooms.

And on a related note, the third person whose thoughts on online education I choose to take very seriously, Seth Godin:

Great guy. Chip and I went to business school together. He was the third youngest person in the class and I was the second youngest person in the class. He got five of us together and every Tuesday night, we met in the Anthropology Department for four hours. We brainstormed more than 5,000 business ideas over the course of the first year of business school. It was magnificent. It wasn’t official, it wasn’t sanctioned. It was just Chip said let’s do this, and we did. And he picked the Anthropology Department because he knew someone there and could get the conference room.

https://tim.blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/138-seth-godin.pdf

That is from an episode from Tim Ferriss’ podcast, in which he interviewed Seth (the whole episode is well worth your time), but the point that I remembered was about small groups.

Anybody who is going to try and do education online is going to have to get small groups going. Without it – in my opinion – it simply will not work.

But how do you form these groups?

I’m still thinking about the how, and the more I think about it, the more it seems as if there is never going to be a perfect answer. Forming groups is hard, and I think we need to make peace with the fact that groups may not always work out.

People won’t get along, people will drop out, quarrels will take place even among groups that develop close bonds – there are many, many things that can go wrong. But it doesn’t matter how long it takes and how many times groups have to be formed and re-formed – it is unlikely that you’ll get an education worth the name without the formation of a group, or community.

And what do these groups do?

… will be the topic of tomorrow’s essay, for I was part of an experiment that tried to answer this question – and I really liked the answer!