Month: December 2022

Exams and Assignments in the Age of AI

The blog hasn’t been updated for a while, but most of his posts make for excellent reading.

What does sociology have to do with exports?

When we designed the undergraduate program for economics at the Gokhale Institute, we were unable to fit in introductory courses on philosophy and anthropology. Among other courses, I should mention – it is not as if the absence of only these courses is my sole regret. But these two pinched more than the others, I’ll admit.

But one course that was included was sociology, and the reaction to it being a part of the syllabus has been mixed. “What is the use of studying sociology?” is a refrain I’ve heard for the past three years, and I wish it weren’t so. Why? Because not all answers to problems in the field of economics lie within the domain of economics.

I’ve long been convinced that “matters of culture” are central for understanding economic growth, but I’m also painfully aware these theories tend to lack rigor and even trying to define culture can waste people’s time for hours, with no satisfactory resolution.

https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2018/12/deconstructing-cultural-codes.html

Tyler Cowen is speaking here of culture, of course, not sociology, but the two are at least related – and in my opinion are practically the same.

But it is all very well to talk of the importance of sociology when it comes to studying economics. But what exactly does it mean?

TCA Srinivasa-Raghavan wonders, in a recent column in the Business Standard, about why India just can’t crack the export problem, no matter what we try:

The latest trade data once again show that India hasn’t been able to solve its export problem. Over the last 75 years, India has succeeded in solving many problems. Food, health, education, low GDP growth rates, and much else. But there is one problem it has been unable to solve — exports.

https://www.business-standard.com/article/opinion/why-does-india-continue-to-have-an-export-problem-sociology-may-answer-122120500165_1.html

At least a dozen committees over 60 years have tried to find solutions. The government itself has been straining hard to provide all kinds of incentives. All manner of policies have been tried. Nothing has worked.

India, despite its amazing businessmen, remains a poorly performing exporting country. Even the success of IT exports is really labour export in a disembodied form.

And, he says, if India’s best and brightest economists cannot solve thhis problem, perhaps we should be looking to other domains. What about, he says, sociology?

For instance, is something about our business communities responsible for this failure? Is it the nature of our political and administrative structure? Or is it a combination of all these things?

https://www.business-standard.com/article/opinion/why-does-india-continue-to-have-an-export-problem-sociology-may-answer-122120500165_1.html

What might be the problem with our business communities? Is jugaad a good thing or a bad thing? Why are we so dependent on, and happy with, the concept of jugaad? Do we take quality as seriously as our competitors? If not, why not? Did our competitors take quality seriously in the past? If not, what made them change?

Is our administrative structure a little too overbearing? If so, why? Is it because of misaligned incentives, as an economist would say, or is there something else “there”? If so, what? What makes our bureaucracy different from those in other countries, from a sociological/cultural viewpoint? Have we always been different?

Not all of these questions have answers exclusively within the domain of economics. It makes sense to study other domains, and ask how the study of those domains enriches your understanding of economic theory. It cuts both ways, of course. While studying those other domains, your study of economics will help you too!

Now, I don’t know, alas, what sociology has to do with India’s poor export growth – if anything at all. But it certainly is a fun question to think about, and is a great example of why studying sociology as a student of economics absolitely makes sense.

One final point. I’m often asked this question by students who are just about starting to learn economics: “What should I read to understand economics better?” They think I’m being deliberately difficult when I answer by saying “absolutely everything that you can read, and not just within the field of economics”.

I’m not, of course. I couldn’t possibly be more serious!

Past posts on EFE that have mentioned sociology can be found here.

On India’s Wu Liu

Wu liu, in Chinese, is “the flow of things”, and is apparently the Chinese word for logistics:

Logistics covers transportation, warehousing and the management of goods. Its Chinese translation, wu liu, literally means “the flow of things”. But that flow within the country is costly and cumbersome. Much of the investment in infrastructure has gone to lubricate exports. Now, as China’s government shifts its focus to consumption at home it is finding that the domestic logistics industry is woefully inefficient.

https://www.economist.com/china/2014/07/12/the-flow-of-things

Logistics spending is roughly equivalent to 18% of GDP, higher than in other developing countries (India and South Africa spend 13-14% of GDP) and double the level seen in the developed world. Li Keqiang, the prime minister, recently echoed industry’s complaints that sending goods from Shanghai to Beijing can cost more than sending them to America.

This is an old report from The Economist – it came out in 2014. I’m not quite sure how much better China’s logistics sector has gotten since then, but back in 2014, India was also able to come up with similar statistics:

Indeed, the Financial Times reported in November 2014 that one French company finds that the cheapest and easiest way to send parts from Bangalore to Hyderabad, a few hundred kilometres apart, is to send them first from Bangalore to Europe, and then back from Europe to Hyderabad. It isn’t as if there isn’t a decent highway between the two cities; but the moment that a truck hit a state border, it has to stop and wait. According to the World Bank, Indian truck drivers spend a fourth of their time on the road waiting at the tax checkpoints that mark state borders. Factor in the time they spend in queues to pay highway tolls, and they spend less than 40 per cent of their time on the road actually driving. And that’s when the roads are good. Moving stuff around India costs this country’s manufacturers more than they spend paying their workers, the FT reports. Even India’s lower-than-low wages can’t make up for the dent logistics costs make in our competitiveness.

Sharma, Mihir. Restart . Random House Publishers India Pvt. Ltd.. Kindle Edition.

As I mentioned, I don’t know how the Chinese logistics sector has evolved since 2014, but India’s logistics sector needs to improve out of sight for us to become internationally competitive. And not just internationally competitive – even when it comes to domestic shipping of goods, there is a lot of scope for improvement:

“At the all-India level, the proportions of the produce that farmers are unable to sell in the market are 34 per cent, 44.6 per cent, and about 40 per cent for fruits, vegetables, and fruits and vegetables combined,” finds the committee on Doubling of Farmers’ Income. This means, every year, farmers lose around Rs 63,000 crore for not being able to sell their produces for which they have already made investments.

https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/agriculture/poor-post-harvest-storage-transportation-facilities-to-cost-farmers-dearly-61047

But, except for cold storage, the country is lagging in all other agri-logistics required to bring the produce from farm to markets. If plugged, the sector can create over 3 million jobs, a majority of which will be at the village level, says the State of India’s Environment in Figures 2018.

Although this seems to be a good show on the state of cold storage in the country, but it should be underlined that the existing cold storage capacity is confined mostly to certain crop types and not integrated with other requirements. In fact, close to only 16 per cent of the target set for creating integrated pack-houses, reefer trucks, cold storage and ripening units has been met. This means, there is an overall gap of about 84-99 per cent in achieving the target on improving the state of storage and transportation of the farm produce. Out of these, the country is far-far behind in meeting the requirement of integrated pack-houses, reefer trucks and ripening units.

And that’s just agriculture. Taken as a whole, the logistics sector in India is rife with inefficiencies, and for many reasons:

A decade ago, the state of India transport and logistics was abysmal. The movement of goods within the country was an arduous and expensive affair. Serpentine queues at Interstate borders, random documentation checks, multiple regulatory checkpoints, tax compliance issues and poor infrastructure meant that India’s trucks had one of the slowest average speeds [20 to 40 kilometres per hour] and lowest distance covered in a day [250 to 400 kilometres] compared to developed countries [60 to 80 kilometres per hour and 702 800 kilometres per day respectively]. It also meant that Indian trucks spent about 60% of their time on the roads. Moreover the logistics sector was a complex beast with more than 20 government agencies, 40 partner government agencies, 37 export promotion councils and 500 certifications. All these factors combined made the cost of logistics in India much higher than most of her big trading partners.

https://twitter.com/anupammanur/status/1577483121183707136

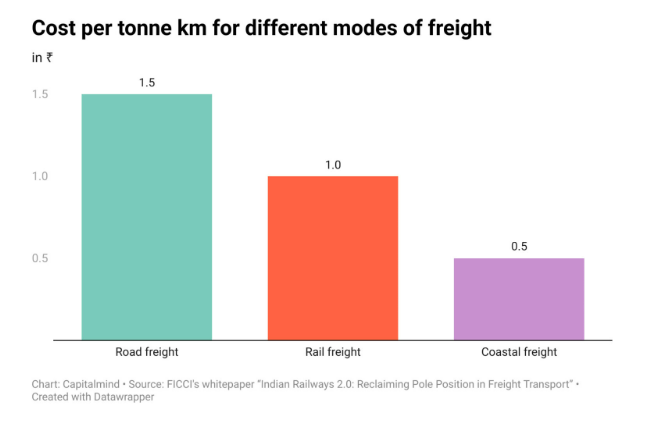

Currently, we transport about 4.6 billion tonnes of goods worth 9.5 lakh crore rupees every year, and we do that through three different ways: coastal freight, road freight and rail freight. I got these statistics from a recent report on the Capitalmind website:

And as the report goes on to say, this break-up is problematic because its much cheaper to transport stuff by rail or by water than road:

Check the third graph in the Capital Mind article to see how the development of the Indian logistics sector defied economics – that is to say, over time, we’ve ended up transporting more by road than by rail! Except, of course, this isn’t in defiance of economics, it is because of it. Last mile connectivity is still poor in India, as most metro riders in this country will tell you. Plus, the fact that we’re transporting people and goods using the same infrastructure is a problem.

All of which is to say that we don’t transport stuff quickly, cheaply and seamlessly in our country. And that’s a amajor reason behind why we are not internationally competitive, and needlessly expensive in terms of domestic consumption. All of us, myself included, would do well to go over the broad countours of our National Logistics Policy. In addition, take a look at the associated e-book, and also read this interview of Vinayak Chetterjee on this issue. If India is to grow as rapidly as possible in the long run (and it must), getting our logistics right is an integral part of the puzzle.

This stuff matters, and if you are a student of economics in India, you absolutely must be familiar with our logistical challenges. They are many, they are inter-related, and solving them isn’t easy.

What Are You Optimizing For, The Software Version

I’m an amateur cook, and not a very good one.

It kills me to say it, and I wish it weren’t so, but I don’t have a “feel” for cooking. You know what I’m talking about of course, because regardless of whether you’ve tried cooking yourself, you have certainly had a meal, and you know what a tasty dish of food is all about. Some cooks have that oh-so-elusive feel for cooking. They know just the right amount of spice that a dish needs, and they know just for how long a dish needs to remain on high heat. They know what the phrase “stop cooking the pasta when it is 80% done” means. The whole armada doesn’t come to a grinding halt for these guys when an ingredient is not to be found in the kitchen. These are the sort of people who will open the refrigerator, grab something else, and nonchalantly say “Ah, this will do just as well.”

I hate those guys.

Me? I’m the mad slapdash cook. My dishes are just the wrong side of done to perfection, and “add salt to taste” in my universe means “fancy a swim in the ocean?”. I, in other words, don’t know when to stop.

But that, it would seem, would make me a good (?) coder. I’m joking, of course. But at least some coders seem to suffer from the same problem: apparently, they just don’t know when to stop.

The article that this picture is from is a lovely little rumination on “feature creep“.

Feature creep is the excessive ongoing expansion or addition of new features in a product, especially in computer software, video games and consumer and business electronics. These extra features go beyond the basic function of the product and can result in software bloat and over-complication, rather than simple design.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feature_creep

It’s ingredient creep in my case, but potatoes, poh-taa-toes.

So why does it happen? Clive Thompson, the author of the piece, comes up with two good reasons:

Granted, some of our problems with feature creep are just pure nostalgia. We fall in love with the early version of an app, and almost like a band’s first album, associate it with a simpl’r time in our salad days; then we get all itchy and pissy when the band moves on. You sold out, man! And for their part, software firms have many excuses for why they shove in all those new features. Users demanded ’em. Sure, only 1% of people use that feature, but they’re crucial users. And anyway, we gotta keep pace with the competition. Swim or die!

https://debugger.medium.com/its-time-for-maximum-viable-product-eec9d5211156

Fair enough. But look — sometimes the enclottification of an app really just is feature creep. And you can understand why it happens! Developers love to develop; marketers want new stuff to market. Adding new features, shipping new code, is fun and exciting. Merely maintaining a successful app? Bleah. So dull.

And how should we avoid falling into this trap? Clive speaks about a concept he calls the “Maximum Viable Product”:

What if more developers developed a sense for the “maximum” number of things a product should do — and stopped there?

https://debugger.medium.com/its-time-for-maximum-viable-product-eec9d5211156

What if more software firms decided, “Hey! We’ve reached the absolute perfect set of features. We’re done. This product is awesome. No need to keep on shoving in stuff nobody wants.”

As he says later on in the article, it is just about having confidence in your amazing design.

As an economist, I would argue that what he is saying is that one should be clear about what one is optimizing for. This could be software coding, this could be an economic policy, or it could be a simple banana bread. But if it is a simple bana bread, maybe stop at the walnuts? Do we really need the cocoa powder, the chocolate chips and the cinnamon powder? And if you pop open the fridge door and begin to think about whipped cream as a garnish, that is what feature creep looks like in the kitchen.

Don’t, not-so-young lad, don’t. Stop. As Clive puts it, this product is awesome. There is no need to keep on shoving in stuff nobody wants.

Decide upon the core problem you are trying to solve, try your best to come up with a near-perfect solution to that core problem, and ignore all of the distractions. It works in the case of software, it would seem, and it also works in the case of policymaking. Always – I repeat, always – be clear about what you’re optimizing for.

And if you’re wondering, the second time around, the simpler banana bread came out much better. My 9 year old sous chef insisted on adding chocolate chips, I’ll admit, but then again, I was optimizing for her happiness.

P.S. If you don’t follow Daring Fireball, John Gruber’s lovely blog, please do. That’s how I came across Clive’s post.

Quick Notes on the World Trade Statistical Review, 2022

If you are a student of economics, you should create a calendar for yourself about important data releases. This could be the release of GDP reports in your own country, it could be the release of the WEO reports from IMF… and if you are a student of international trade, your data release calendar aboslutely should include the World Trade Statistical Review from the WTO. Pro-tip re: the WTO – you’ll learn much more by spending a day drinking coffee and going though as many links as you can stand to from here. The coffee is important, trust me, and it really helps if you can do this with a friend going though the same exercise with you (but on a separte device, mind you).

But back to the World Trade Statistical Review: this year’s report is really important for obvious reasons. We get a look at how the world recovered from the pandemic, and we also get a sense of how 2022 has unfolded, given all of what this year has given us in terms of momentous events.

First, the obvious stuff. The year-on-year change in terms of world trade in both goods and services saw a remarkable recovery in 2021. We also saw a bit of tapiering off in 2022, relative to 2021. China, the US and Germany (in that order) were the three largest merchandise traders. If you are a student of the Indian economy, you absolutely should ask where India stands in the list. The answer is to be found in Table A6, pp 58 of the report. You can also download the associated Excel file from the World Trade Statistical Review website (the link is in the first paragraph above).

Note also that the appendix si worth going through in order to get a sense of how India fares in other dimensions of international trade. Open up the PDF, and do a CTRL-F for India, and see what you might wish to take note of. Me, for instance, I found it fascinating that in terms of percentages of world merchandise exports, we touched 2.2% in 1948, and have not crossed that level (or even matched it) ever since. That is from Table A4. I also found it interesting that India, more than any other nation, did remarkably well in terms of IT exports (pp. 31). The commodity specific export data related to India in the appendix is also faascinating, and if you really want to get into the weeds of the report as a student of the Indian economy, I think you will find it to be worth your while.

The global exports of digitally delivered services on pp 17 is a fascinating chart, and one that Timothy Taylor has spoken about on his blog.

Ask yourself if you know how to create the kind of chart that you see on pp 18.

Note the impact of the war in Ukraine on international trade in chart 3.3, pp 24. But also take a look at chart 3.8

Ask yourself why the price of natural gas is falling off with the advent of winter in 2022. Should it not be even higher, now that winter is setting in? Ask yourself what you have not understood about trading, futures and finance if the answer escapes you.

Ask what’s up with Japan when you look at chart 3.5.

Compare China and India in chart 3.10, pp 31

Go to pp 43 of the report. Are you familiar with what SITC means? What about HS codes? Update: hereticindian, in the comments, shares this very useful link: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/classifications/Econ

More fun awaits you on pp 45: what about BPM6? What about SNA?

How familiar are you with the list of sources given on pp 50? Do you regularly visit these website? If you are a student of economics, you should have all of these bookmarked, and you should have a degree of familiarity with at least some of these sources.

“What should I read to prepare for placements?” is the wrong question to ask.

“What, of all of what I’ve been reading over the past five years, is the most relevant to placements?” is the better question to ask. Get in the habit of reading far and wide, and get in the habit of familiarizing yourself with the relevant data sources in your field.

The correct time to start on this? Yesterday.

Duolingo, Gamification and Habit Formation

I got “promoted” on Duolingo recently, and today’s blogpost is about how weirdly happy I feel about it.

I am an incredibly lazy person. We all are to varying degrees, I suppose, but I’m convinced that I do putting off and procrastrination better than most. There are a few things that I do with enthusiasm and something approaching regularity (writing here being one of them) but with most things in life, tomorrow is a better day for me than today.

There is a very short list of things I am compulsively addicted to doing on a daily basis, There’s Wordle, for example. Reading blogs, for another. The NYT mini crossword, and some other stuff. But there is a clear winner on this list: Duolingo.

On Duolingo I have a 753 day streak, and counting. That is, I have practised on the Duolingo app for 753 days and counting. And it’s not because I am awesome at showing up regularly – it is because Duolingo has incentivized me to show up regularly, and here’s how they do it.

First, peer pressure. Duolingo allows you to follow people in your contact list who are also on Duolingo, and it’s a two way street. That is, they can follow you too:

AshishKulk is my user ID on Duolingo, and please feel free to “add” me to your network if you are so inclined. I can always do with more peer pressure! Knowing that my friends are practising more than I am is a great incentive to try and keep up – which, of course, is what peer pressure is all about.

The score-keeping mechanism in Duolingo is XP. The app tells you how much XP you “acquired” on a daily, weekly, monthly and all-time basis.

Each of these frequencies is gamed differently. For the all time streak, you can check where you rank among your friends (I’m third, if you’re wondering). For the monthly score, Duolingo hands out “badges” if you earn a certain number of XP in a month:

For weekly streaks, you get promoted to different “leagues” based on how many points you score on a weekly basis. It is a double edged sword: you also get “demoted” if you don’t practise enough in a week. The leagues start and finish every Sunday afternoon India time, and I’m typing this out on a Sunday morning – wish me luck!

And the daily basis is perhaps the best gamification of them all, because you end up in a contest with yourself. How long can you keep your daily streak going? Like I said, mine is at 750 odd days, and I got “promoted” for it:

There are also daily quests, friend quests, stories involving characters that build a more personalized, relatable learning experience, and recently, learning paths that use spaced repetition to make sure that weaker concepts are revised and firmed up over time. You can “buy” streak freezes to “protect” your streak in the Duolingo store. These artefacts can be “purchased” using “gems”, and that’s yet another gamificaiton story.

Long story short, the Duolingo team goes out of its way to try and keep you hooked on to learning, and I’m here to tell you that it has definitely worked in my case.

And that’s the point of this post, really. I think Duolingo to be an exemplar when it comes to gamification, but the meta-point here is an obvious one: how do we all go about gamifying activities in our life that we wish would turn into habits? How about a Duolingo experience for exercise? Meditation? Learning cooking? Financial habits?

There are those among us who can build out habits in their lives without gamification, of course, and I envy them for it. But for those of us who are paashas of procrastination, such a tool can help us get better at showing up more regularly.

I speak from personal experience when I say this, though: Duolingo has done it better, and been more effective, than any other habit forming app that I have tried.

Now, excuse me while I go and try to stay in the Diamond League!

Pick Up A Bottle of Rice With a Chopstick

And a bonus, on a related topic:

An Appropriate Continuation to Monday and Tuesday’s Posts

The Art of the Adda: Is an EFE MeetUp A Good Idea?

You learn best when you debate, discuss and disagree.

That’s my shtick at the start, and throughout the entire semester of any course that I’m teaching. A prof yapping away while standing at the lectern, and students paying closer attention to the time than to the prof is the worst way to learn. Unfortunately, it is this that is far more prevalent than the d,d and d strategy, and more’s the pity.

Which is why that adda I spoke about yesterday was so much fun, at the Fat Labrador Cafe. I’m betraying the fact that I’m married to a Bengali when I speak of the art of the adda. While katta is a word that a Maharashtrian would prefer, I’ve always had an attraction for alliteration, so I hope you’ll allow me my little word-play.

But back to the adda: Anupam Manur from the Takshashila Institute in Bangalore was in town for a conference, and he and I regaled a small but extremely enthusiastic audience with our list of five under-rated/counter-intuitive ideas from the field of economics.

The point isn’t about which were his five and which were mine – at least, that’s not the point of this post. The point is that fun laid-back discussions about any topic is a wonderful way to learn, to network and to have fun. And when accesorized with coffee that is as good as the one that The Fat Labrador Cafe serves up, well, what more can one ask for?

It is December, so why not try out something fun? This is addressed to folks who are in Pune (to begin with). How many of you would be interested in meeting up for an adda on the 11th of December, at 6 pm? The topic I have in mind are three posts that I really enjoyed writing this year, about learning economics by watching movies, paintings and cricket.

No money in and no money out, to be clear – this is not a paid event, this is very much a group of people getting together for a relaxed conversation. If we meet at, say, The Fat Labrador Cafe, each one of us pays for our own beverages and food. The idea is to learn through debate, discussion and disagreement (the non-Twitter variety, just to be clear). Around ten to fifteen people would be ideal, I think, so if I hear back from enough people, I’ll be more than happy to coordiante and make this happen. Feel free to reach out via this form.

When:

11th December, 2022 at 6pm

Where:

The Fat Labrador Cafe.

What:

An adda about fun ways to learn and apply economics.

Do I need to know economics?

Gawd no. But an interest in movies OR cricket OR art will help. Even this ain’t mandatory!

What do I need to pay?

Nothing, except an investment of your time. And you need to pay for whatever you eat/drink at the cafe