The Penny Drops

Imagine this:

Let’s say a young man calls you up. Could be your cousin, or your nephew.

I’ve got a problem, he says.

Temme, you say.

Well, it’s like this, he says. I work in an MNC in Bangalore, and make a lot of money.

Great, you say. What’s the problem?

Well, I stay with roommates, and it’s complicated. We were all together in college, and we’d sworn while in college that we’d be roommates. Problem is, all my friends earn nowhere near as much as I do. We’d sworn to live as one big happy family, so we’re all staying together, and that’s awesome. But…

Yeah, you say. But what?

Well, our motto was and is “All for one and one for all”. The problem is that what that ends up meaning is I contribute a lot to run our home, because I earn a lot more than the others. My contribution goes into a common “kitty”, proportionate to how much I earn. We all contribute half of our salary to run our home, but because I earn much more than the others, I contribute much more.

So what’s the problem, you yawn. If you contribute more, you should also get a bigger say in how that money is to be spent, no?

But that’s the problem!, comes the response from the other side. How the money is to be spent is not up to me. There, the principle is one person, one vote.

Wait a minute, you say. When it comes to pooling in the money, it is a function of what you earn. But when it comes to distributing the money, it is a function instead of how many of you are there?

Exactly, says the young, troubled whippersnapper. Now what?

If you contribute more, should you (or should you not) get a greater say in how your contribution is to be spent? And if not, should you be contributing more in the first place?

What is fair, what is just, what is desirable, and what is best? And for whom?

I don’t know if you’ve noticed, but there has been a bit of a kerfuffle recently about southern states saying it’s all very unfair. What exactly is unfair, you ask? Buckle up, because this is going to be a long ride.

The Background

Like I said, this is going to be a long story, but because this is one of the most important things we have to tackle as a country, let’s set about learning more about it. Let’s begin with the 42nd Amendment to the Indian Constitution:

Up until 1976, after every Indian Census the seats of Lok Sabha, Rajya Sabha and State legislative assemblies of India were re-distributed respectively throughout the country so as to have equal population representation from every seat. The apportionment was done thrice as per 1951, 1961 and 1971 population census. However, during The Emergency, through Forty-second Amendment the government froze the total Parliamentary and Assembly seats in each state till 2001 Census. This was done, mainly, due to wide discrepancies in family planning among the states. Thus, it gives time to states with higher fertility rates to implement family planning to bring the fertility rates down.

Even though the boundaries of constituencies were altered in 2001 to equate population among the parliamentary and assembly seats; the number of Lok Sabha seats that each state has and those of legislative assemblies has remained unaltered since 1971 census and may only be changed after 2026 as the constitution was again amended (84th amendment to Indian Constitution) in 2002 to continue the freeze on the total number of seats in each state till 2026. This was mainly done as states which had implemented family planning widely like Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Punjab would stand to lose many parliamentary seats representation and states with poor family planning programs and higher fertility rates like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Rajasthan would gain many of the seats transferred from better-performing states.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delimitation_Commission_of_India

What does this mean, and why does it matter?

Let’s talk about a Lok Sabha constituency from Tamil Nadu, and a Lok Sabha constituency from Uttar Pradesh. If the Lok Sabha Member of Parliament (MP) from Tamil Nadu represents a 100 people (let’s assume this), how many people should the Member of Parliament from UP represent?

Should it be around the same number, 100? Is a little bit more OK? Is a lot more OK? At what stage do you say “whoa, this is too much!”? Let’s rephrase the question: should each state in our country send the same number of Members of Parliament to the Lok Sabha, or should larger states send a higher number of MPs? Larger defined in terms of total population, please note.

And one of the tenets of democracy is that each Member of Parliament should represent roughly the same number of people. We can’t have – or shouldn’t have, at any rate – a very large number of MPs representing very few people. Nor should we have a very small number of MPs representing very many people.

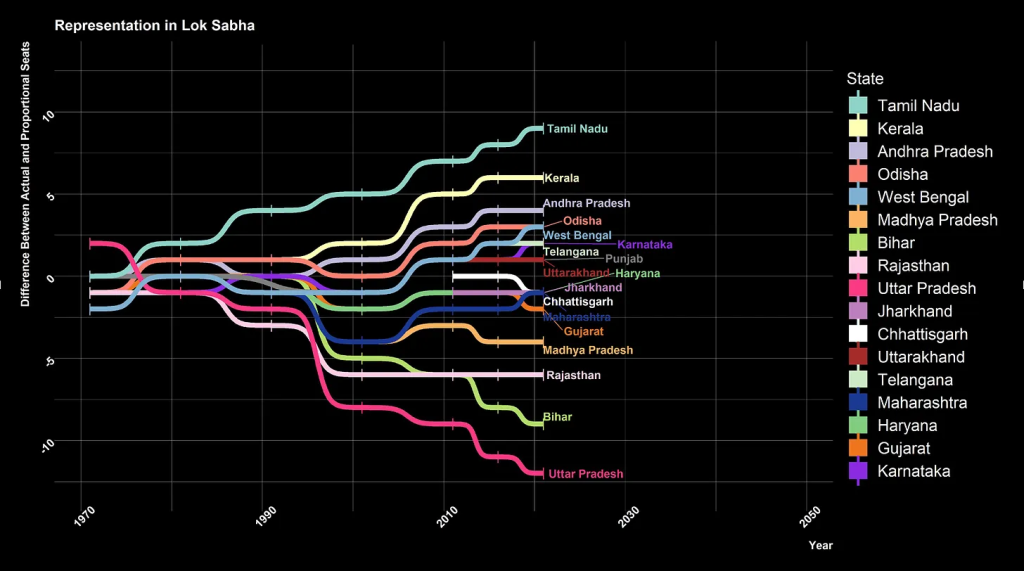

This chart has been taken from Shruti Rajagopalan’s excellent essay, called Demography, Delimitation and Democracy. And what is shows us is one way to answer the question I have raised above. By her calculations, when the delimitation freeze ends*, Uttar Pradesh will have 12 to 13 seats short of what their population should merit. Or put another way, Tamil Nadu will likely have 11 seats more than what their population should merit.

Here’s another way of thinking about this: if a state has (say) x% of a country’s population, it should have (say) y seats in the Lok Sabha. If that be so, another state that has 2x% of a country’s population should have 2y seats in the Lok Sabha.

Why? Because otherwise, the second state will have a smaller number of MPs arguing for it in the Lok Sabha – smaller relative to the number of people in that state. And the first state, of course, will have a larger number of MPs representing that state in the Lok Sabha – a larger number relative to the number of people in that state.

As Shruti puts it in her essay:

One aspect of the “one person, one vote” concept, as envisioned by Ambedkar, was about granting every single Indian over 18 the right to vote in elections. India has adopted universal adult franchise since the birth of the republic in 1950. But to give the principle of “one person, one vote” any meaning, constituency sizes must be roughly equal. The random circumstance of being born in Bihar means that the constituency size is about 3.1 million, but if the same person is born in or moves to Kerala, the value of their vote increases because the constituency size is 1.75 million.

https://srajagopalan.substack.com/p/demography-delimitation-and-democracy

So in essence, each state should send a proportionate number of MPs to the Lok Sabha. And the number of these MPs should be proportionate to what? To the percentage share of the total population in each state. That way, we can make sure that each state gets proportionate representation in the Lok Sabha. Right now, there is an imbalance – the people of Tamil Nadu are over-represented, and the people of Uttar Pradesh are under-represented.

Of course, Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh are used to represent, generally speaking, states in the less populous south and the more populous north respectively.

What is the scale of the problem?

Right, now that we have established this, let’s ask the next obvious question: how many people are there in each state in our country? Here’s one way to answer that question:

Here’s another way of putting it – the Indian Prime Minister is in effect the Prime Minister of the populations of all of these countries put together.

You know how we keep saying that hey, we have one-sixth of the population of the world in our country, and it is therefore unfair that we don’t have a permanent seat on the UN Security Council?

Uttar Pradesh can say the same thing (kinda – you know what I mean), but at the national level.

So What Are We Waiting For?

Well, ok then, a layperson might say. All this is good to know, and er, carry on and all that – but why don’t we just go ahead and, you know, change the distribution of the seats in the current Lok Sabha? If UP gets to send 84 MPs to the Lok Sabha, up that number. And If Tamil Nadu gets to send 39 MPs, well, adjust that number downwards. What’s the problem?

Well, the endowment effect, for starters. But more importantly, it’s all well and good to talk about demography and all that, but this is, after all econforeverybody. Sooner or later, rokda must enter the building.

How does this country of ours function when it comes to finances? Well, back when we got independence, we decided that we would organize finance in the following way – states would get to levy some taxes, and they could spend that tax revenue on stuff they were responsible for, such as health, among other things. We call this Own Tax Revenue. The Union government would get to levy some taxes, and part of this revenue would be kept for the Union Government’s expenses (army related expenditure, for example, among other things). And there’s other complications, but we’ll skip that part for now.

But ah, there is a small part of one of the sentences in that last paragraph that hides a world of pain. Note that I said “part of this revenue would be kept for the Union government”. Now, the part that is not kept for the Union Government – how is it distributed to the states?

For example, let’s say the Union government collects 100 rupees in taxes.** How much should it keep with itself? Should it keep 40 with itself and give the rest to the states? Or should it keep 80 with itself and give 20 to the states? Or some other number? How do we decide? How should we decide?

Dr. Arvind Panagariya and his band of merry men and women shall answer this question for us in the months to come, as mandated by the law. They shall answer two questions (and do a whole lot of other things too, of course!)

- How much should the Union government keep with itself?

- Of what can be distributed to the states, which state should get how much, and why?

It is that second question that is tricky. Oh so very tricky. And figuring out how best to answer it is, as it turns out, what we’re all waiting for.

So How Do We Decide Which State Should Get How Much?

Of all of the taxes collected by the Union government, we first have to decide the split between what the Union Government keeps for itself and what is given to the states. This is called Vertical Devolution.

Then, of what is given to the states, we have to decide how much each state gets. This is called Horizontal Devolution.

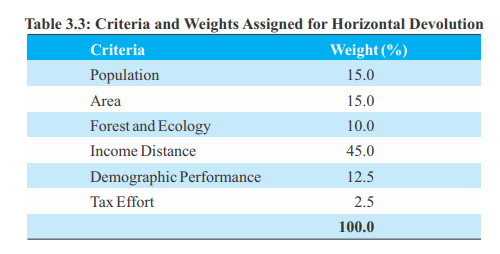

The predecessors to Dr. Panagariya’s merry band came up with this formula:

The higher the population in a state, the more it should get when it comes to horizontal devolution. How important is this idea? It gets 15% weightage.

The larger the physical area of a state, the more it should get (15% weightage)

The greater the forest cover in a state, the more it should get (15%)

The poorer a state compared to average incomes in our country, the more it should get (45%)

The better a state at lowering it’s Total Fertility Ratio (demographic performance) the more it should get (12.5%).

The better it is at mopping up taxes, the more it should get (2.5%).

So while other factors apply, as they should, the primary consideration is this: the poorer a state, the more help it should get.

“Well, of course” you might say, channeling your inner Mahi.

And your inner Mahi would be right, of course. This is how it should be. Except, as our little story at the start of this blogpost helps us understand, it is a bit more complicated than that.

This is a multi-part series, to be continued! In later posts, we shall learn about how to think about this problem from an economic perspective, and how to think therefore about resolving the problem. But this point is worth emphasizing: if you are an Indian citizen, you should be thinking long and hard about this issue.

*Quite when the delimitation freeze will end is a matter of some conjecture. As Shruti says in her blogpost: “The Eighty-Fourth Amendment extended the 1971 census freeze on the total number of seats per state in the Lok Sabha/state legislatures until the publication of the census figures after 2026 (which is expected in 2031, unless the 2021 census is delayed so much that it is only published in 2026).”. I’ll go a step further and say that there is no guarantee, of course, that the 2031 census will be conducted as per schedule.

** How it collects these taxes is a story involving VAT, MODVAT, CENVAT, GST and other horrific acronyms. As with other inconvenient acronyms (such as, say, CRS) so with these acronyms in this blogpost. We shall simply assume that they don’t exist for now.